Traffic

Steven Soderbergh's Traffic concerns the interlinked drug trade and drug war as they ebb and flow across the US/Mexico border.

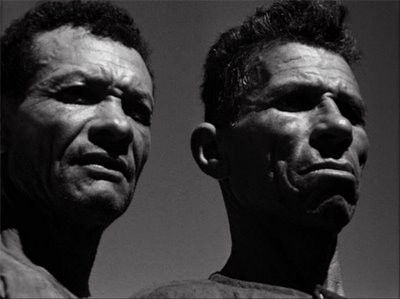

Steven Soderbergh's Traffic concerns the interlinked drug trade and drug war as they ebb and flow across the US/Mexico border. The film plays up cinema's basic hybridity. It bridges the worlds of Hollywood and independent cinema (of popular and "legitimate" culture): it has a Hollywood budget ($49 million) and mainstream stars, but is shot with self-conscious idiosyncrasy (above all in the use of coloured filters and extremely grainy film) and stylistic nods to avant-garde and nouvelle vague directors (Richard Lester, Jean-Luc Godard).

Further, it straddles the linguistic border between Spanish and English: the dialogue is more or less evenly divided between the two languages. Traffic is itself almost a bicultural product; or at least it shows off Hollywood's powers of simulation and performativity, at the same time as it warns of the dangers of such smooth chameleon-like characteristics. Above all, the movie points to, and to some extent inhabits, a cultural and political space traversed by unstable and inconstant (but inevitable) transnational flows of commodities, discourses, and power.

The film's plot--or rather, three interlinked plots--points to the difficulty of distinguishing between latinidad and Americanism. The flow of drugs makes a mockery of border controls and class insularity: newly appointed US drug czar Robert Wakefield (played by Michael Douglas) soon finds that what he has regarded as a Mexican problem of supply and a lower class, black problem of consumption threatens to blow apart his own, comfortably well-heeled, family. As his teenage daughter Caroline (Erika Christensen) descends into addiction, Wakefield traces the network that joins Tijuana, Mexico, to downtown Cincinnati, Ohio, and the privileged suburbs.

Meanwhile, Helena Ayala (Catherine Zeta Jones) discovers that her all-American lifestyle in Southern California is bankrolled by drug money and Mexican contacts; to maintain the round of picnics and parties, and to keep her family intact, she too has to follow the drugs trail back south of the border. In initiating a new form of drugs transportation, using dolls made out of moulded cocaine, Helena signals a shift whereby this illegal traffic is no longer hidden within other commodities: rather, the flow of drugs now permeates the very fabric of mass culture.

In tracing Helena's crossing from a California rendered in idealised Technicolor to a Mexico portrayed cinematographically through a tobacco-coloured filter, Traffic reveals that what makes Mexico apparently distant in its Latin American exoticism and corruption is, precisely, a filter in the viewer's (camera) eye, rather than an essential difference between "Anglo" and "Latino." "No one gets away clean," as the film's advance publicity had it, however much the First World may wish to insulate itself from the Third. Traffic highlights simultaneously the way in which we see things differently according to our own context and presuppositions, and also the invisible but all too evident threads that form ever-shifting networks traversing national or local contexts.

These new networks undermine one set of differences only to construct new and more unstable hierarchies of power; above all, here, the power to determine characters' life and death is exercised in almost random and unpredictable ways.

Traffic can stand still (or be jammed), but its essence is motion and the drive to circumvent obstacles. Negotiating traffic successfully requires an awareness of its changing direction and its rhythms. This film neither celebrates this unpredictable flow, whose immanent transactions and logics pass mostly under the radar of state hierarchies, but nor does it condemn it. Indeed, it demonstrates the futility of the kinds of condemnation parrotted by the "war on drugs" (and now the war on terror).

As Wakefield notes, giving up on his cliché-ridden speech and walking out of his White House press conference at the end of the film, the other is no longer external, "out there." It resides at the very heart of mainstream US society.