It's All True

A surprisingly high proportion of Orson Welles's few films deal with Latin America: Touch of Evil, of course, but also for instance The Lady from Shanghai and Mr Arkadin.

A surprisingly high proportion of Orson Welles's few films deal with Latin America: Touch of Evil, of course, but also for instance The Lady from Shanghai and Mr Arkadin.But it is It's All True that would have been Welles's most significant exercise in cinematic latinidad. Urged on by Nelson Rockefeller, Co-ordinator of "Inter-American Affairs," in 1942 Welles went down to Rio to make a film that would help undergird the US's "good neighbour" policy towards Latin America.

A plan emerged that the film would consist of three relatively independent sections: one, "My Friend Bonito," set in Mexico and about a child's relationship with his donkey; another, this time in colour, about the Rio Carnival; and a third, now back in black and white, about the epic 1600-mile sea voyage of four fisherman from Fortaleza to Rio de Janeiro.

But the film was never completed: the Brazilian government of Getúlio Vargas became skittish about Welles's increasingly politicized representation of Carnaval; one of the four fishermen was drowned in the bay off Rio; and RKO pulled the plug.

An incomplete episodic film about Latin America by one of cinema's great directors... the comparisons with Eisenstein's ¡Que Viva México! abound. And they don't stop there.

The one more or less complete section of It's All True that remains is "Four Men on a Raft," the story of the jangadeiros' epic trip to demand their inclusion within the nation. The raw footage was found only in the 1980s, and was edited together after Welles's death. But it's not simply the editing that gives the impression that this 20-minute short is a homage to (or even pastiche of) Eisenstein's Mexican film.

The theme might have been lifted straight from the Russian director's notebooks: we see rural peasants who respond to tragedy and oppression by aspiring to become historical agents, legitimate members of the national community. (Ironically, here Welles is more populist than the populist leader Vargas: the risk of populist politics is that it is always liable to be outflanked by other populisms.)

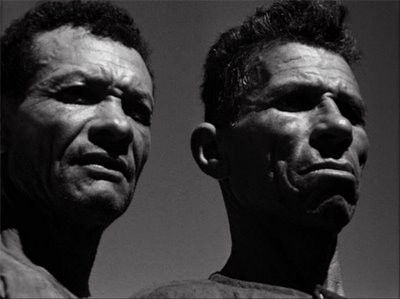

The camerawork is also pure Eisenstein: composition and mise en scène are paramount. Those who regard classic Welles cinematography to be the long takes and complex camera movements of Touch of Evil are in for a surprise. Here the camera hardly ever moves. Rather, it takes up a fixed position (usually from a low angle, sometime from above, hardly ever at eye level) and allows the characters to enter and leave the frame, emerging from and returning to the landscape. There are very few (if any) interior shots, and often we have human figures shot from below silhouetted against a cloud-strewn sky that takes up at least two thirds of the frame.

Moreover, relatively little of the film is in medium shot: we either have long shots (of landscape or masses, often both) or tight close ups on faces. The few medium shots, such as of preparations on the beach or sailing on the boat, are crowded with human forms and activity that bursts out of the frame.

And as for the close ups... In Herbie Goes Bananas we heard the character Captain Blythe declare "I love your country. It's very colourful, and the children have such expressive faces." Ironically, the children of whom he's speaking have almost completely blank, inexpressive faces, and the camera spends very little time examining them. But his comment is wonderfully apt as a description of the cinematography of Eisenstein and (above all) Welles.

In It's All True it's the "Carnaval" section that would have been a study in colour. (In ¡Que Viva México it's the "Fiesta" section, though there texture has to stand in for colour in what's a purely black and white movie.) But much of "Four Men on a Raft" (like much of Eisenstein's film) is a study in the expressivity of the human face.

And what's at issue here is indeed expression rather than signification. It's not that these faces signify determination or despair, fear or joy, tenderness or concern (to name just some of the affects that pervade this film). Rather, they are to express something of the affective essence of the characters and individuals portrayed. Welles's close ups are studies in incorporated expression.

We're not meant particularly to wonder what (if anything) might be behind the expressions: these faces are monuments rather than windows. When they change, their motility is a change of state, the expression of a distinct essence, rather than a new aspect of the same subjective identity.

But is this not true more generally: that when Hollywood goes Latin, it reveals itself to be a cinema of expression, to be engaged affectively, rather than a cinema of signification, to be decoded linguistically.

See also Lawrence Russell on It's All True at Film Court. And Wellesnet for "discussion of all things Orson Welles."

Labels: expressivity, orson welles