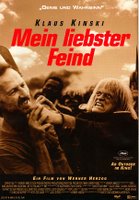

My Best Fiend

My Best Fiend is ostensibly Werner Herzog's film about Klaus Kinski. But it is soon clear how much it is a film about Herzog himself.

My Best Fiend is ostensibly Werner Herzog's film about Klaus Kinski. But it is soon clear how much it is a film about Herzog himself.Herzog tells us endlessly about Kinski's madness, his fits, his ravings. But Herzog protests too much. He talks too much. He raves.

An early sequence is paradigmatic: in what used to be the boarding house where the young Herzog and the young Kinski once lived together, a building that has now been renovated and turned into a swish bourgeois home, Herzog goes on at far too much length about Kinski, his eccentricity, his obsessiveness. The building's current owners start tuning out. It is Herzog who has begun raving, allowing his own obsessions to dominate the screen.

The various other people we meet--such as the actress Eva Mattes, the still photographer Beat Presser--all seem to have heard Herzog's schtick before, and treat him warily, carefully, respectfully. " You would also have been a good Fitzcarraldo," says Presser cautiously, measuring his words, watching Herzog for his reaction. But of course it wasn't Herzog. It was always Kinski who was Fitzcarraldo (even though Jason Robards was Herzog's original choice).

The madness is Herzog's, however much he spends the entire film performing reasonableness, recounting his patience in the face of the untamed beast that was Kinski.

And the mourning, for this is a film that is a prolonged work of mourning, the mourning that is Herzog's despair at being without Kinski, that he can only fill with a torrent of words, of recrimination. It is as though finally he also blames Kinski for leaving, for leaving his friend (his fiend) alone again.

So much of Herzog and Kinski's relationship played itself out in Latin America. They fought each other against the backdrop of an encroaching, suffocating sense of Latin America as a natural force that threatened always to overshadow the puny rages of these all too human f(r)iends.

"Between Kinski and me there was an unbridgeable gap," Herzog tells us. "This had to do with his feeling for nature." And then we see archive footage of Herzog, for almost the only time in this film, talking in English. It is during the filming of Fitzcarraldo, in Amazonian Peru:

Of course we are challenging nature itself, and it hits back. [. . .] And that's what's grandiose about it and we have to accept that it is much stronger than we are. Kinski always says it's full of erotic elements. I don't see it so much as erotic, I see it more full of obscenity. It's just that in nature here it's vile and base. I wouldn't see anything erotic here, I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and . . . just rotting away. Of course there is a lot of misery, but it's the same misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery and the birds are in misery, I don't think they sing I think they just screech in pain. Taking a close look at what's around us there is some sort of harmony. It is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. But when I say this I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It's not that I hate it; I love it, I love it very much, but I love it against my better judgement.It is Kinski himself who is also, of course, this uncontrollable natural force, "much stronger than we are [. . .] full of obscenity," that Herzog loves "against [his] better judgement."

But it is the jungle that, as so often, is the figure for the psyche, exemplifying our impossible (but unavoidable) relationship with the other.