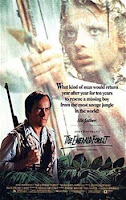

The Emerald Forest

John Boorman's The Emerald Forest sets out to make the invisible visible, all the time aware of the dangers and perhaps the unethical inconsideration involved in precisely such an ambition. This contradiction is of a piece with the paradox of making a film, especially a film that purports to venture deep into the rainforest, that claims to protest the way in which technology denudes the natural world. It's one of the first eco-adventure movies with an environmentalist and subalternist heart, but it remains uneasy with the tensions that this very genre entails.

John Boorman's The Emerald Forest sets out to make the invisible visible, all the time aware of the dangers and perhaps the unethical inconsideration involved in precisely such an ambition. This contradiction is of a piece with the paradox of making a film, especially a film that purports to venture deep into the rainforest, that claims to protest the way in which technology denudes the natural world. It's one of the first eco-adventure movies with an environmentalist and subalternist heart, but it remains uneasy with the tensions that this very genre entails.The "invisible people" are an Amazonian tribe that have so far evaded contact with Western civilization. But all around them they sense that their world, the world as they put it, is rapidly growing smaller. And this contraction is thanks in no small part to the efforts of people such as Bill Markham, a US engineer down in Brazil to clear the land and dam the river. But one day, as though in righteous vengeance, the invisible people snatch Markham's son Tommy as he and his family are sitting down for a picnic at the site of the future degradation. So Tommy too becomes invisible, and remains so for the subsequent decade that Markham and his wife anxiously comb the forest for any sign of him or his kidnappers.

Markham decides to take one more trip upriver, armed with the feathered arrow that was all the Indians left behind, an obnoxious German reporter by the name of Uwe, and rather foolishly as it turns out also with an M-16 carbine. He and the reporter fall into the hands of another tribe, the so-called "fierce people" who understandably live up to their name when provoked by Markham's semi-automatic. Uwe dies a grisly and unmourned death, while Markham sets of running, pursued by savages. Fortunately it's at this point that he finally runs into Tommy, who now goes by the sobriquet Tomme and is a fully-fledged member of the invisible peoples' tribe.

So where the father had thought to save the child, it turns out that it is Tomme who rescues the man he now calls Dad-dee to distinguish him from his adoptive indigenous father, the tribal chief Wanadi. And Wanadi in turn, sage and sensitive in line with his close empathy with nature, cures Markham of the wounds sustained in his escape from the fierce people. Unfortunately, however, the interloping Westerner has caused more damage than the few scrape he suffered. Along the way he dropped his gun, which the invisible people's enemies are keen and quick to learn to use against them.

So where the father had thought to save the child, it turns out that it is Tomme who rescues the man he now calls Dad-dee to distinguish him from his adoptive indigenous father, the tribal chief Wanadi. And Wanadi in turn, sage and sensitive in line with his close empathy with nature, cures Markham of the wounds sustained in his escape from the fierce people. Unfortunately, however, the interloping Westerner has caused more damage than the few scrape he suffered. Along the way he dropped his gun, which the invisible people's enemies are keen and quick to learn to use against them.Tomme has no interest in returning to his former life in the city, so Bill leaves the forest empty-handed. But when the invisible people come under attack from their M-16-weilding neighbors, who take their womenfolk and send them on into prostitution, not even the old man Wanadi's curative powers can save the day. So Tomme has to leave the forest in search of his biological father who alone can help the tribe rescue their women now dramatically on display for drunken Portuguese-speaking Brazilians in a decrepit brothel at the frontier between the two worlds.

The rescue accomplished, Markham once again tries to convince his (former) son that he should emerge from the jungle, pointing out that the nearly-finished dam that he himself has designed means that further encroachment on their territory is inevitable. And once again Tomme refuses. But both in their own way are now determined that the dam has to be destroyed, so that the Indians can fade back out of sight. The indigenous resolve to employ magic, conjuring up frogs to call down torrential rain; Markham takes a few sticks of dynamite for the same purpose.

And in the end it is not technology that saves the day. The frogs do their stuff while Bill's detonator fails to go off. Yet this is a somewhat limited view of technology, of course: the frogs, too, and the hallucinogenic drugs that the indigenous take to call them forth, not to mention the green stones they employ for their (rather fetching) face and body paint are all technologies in their own way. Presumably Boorman would argue that film can be such a liberating technology, in opposition to the destructive machines that are tearing down the Amazon's trees and threatening indigenous livelihood. But even guns have their uses, as the brothel shootout showed. So the movie displays more an anxiety about its own mechanisms, as well as a certain seduction for the emerald aesthetic of the forest and its peoples, rather than any real sense of how that anxiety could be soothed.

YouTube Link: frolics in the water (French subtitles).

Labels: contradiction, indians