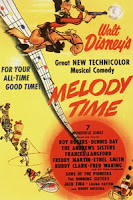

Melody Time

Watching Melody Time is a reminder of how very, and rather surprisingly, odd Disney can be. Nowadays Disney is so fully woven into popular culture and everyday life that it has lost much power to shock. Moreover, Disney has changed over the years. But in the 1940s the strangeness of animated cartoons must still have been apparent; although in other ways the films of what Michael Flint terms Disney's "weird years" were very much of their time.

Watching Melody Time is a reminder of how very, and rather surprisingly, odd Disney can be. Nowadays Disney is so fully woven into popular culture and everyday life that it has lost much power to shock. Moreover, Disney has changed over the years. But in the 1940s the strangeness of animated cartoons must still have been apparent; although in other ways the films of what Michael Flint terms Disney's "weird years" were very much of their time.The very notion of animation, putting a voice or feelings to an inanimate object, is uncanny from the start. The famous "Sorcerer's Apprentice" sequence from 1940's Fantasia is an allegory of the possibly sinister consequences of this power to give apparent life to things. Even the somewhat more benign gesture of anthropomorphizing animals (a mouse, a duck, a dog) can be perturbing: even as it makes them more like us, the sense of a difference between human and animal never quite disappears. And the entire Disney enterprise is certainly a break from realism, which could be regarded either as a return to some archaic notion of the magical or as an investment in more modern conceptions of the surreal, of the fears that plague our cultural unconscious.

Over time, Disney and Disneyfication has become more familiar, both in the ways in which it is received and in the ways it portrays itself. But Melody Time is a good example of the ways in which, at least earlier during the last century, the corporation was torn between a homely version of mass culture on the one hand, and a rather more experimental adventure into the avant garde on the other. And there is little attempt to unify these tendencies or make them cohere by means of some over-arching narrative: Melody Time gives us seven short, unconnected sequences that never quite come together.

The homely is represented here by the first sequence, a Winter scene of two lovers skating on a lake and then, with the help of some animal friends, avoiding near disaster. Also, in more ideological vein, we're presented with a sequence that provides a romanticized vision of the American folk hero Johnny Appleseed, complete with Indians dancing in harmony with white settlers in celebration of the apple harvest. But another sequence, featuring a jazzed-up version of Rimsky-Korsakov's "The Flight of the Bumble Bee" is very different. The bumble bee in question is half-terrorized by an increasingly abstract set of animations: nightmarish flowers, a prison-like stave, and falling piano keys, all to a combination of Russian classicism and American boogie woogie.

In short, the film problematizes Peter Berger's famous account of modernism as constituted by a sharp scission between mass culture and avant garde. Disney's modernism combines aspects of both. And while we have become accustomed to Mickey and friends permeating mass culture, the vanguardism returns with a shock when we watch a film such as Melody Time.

Perhaps it is by realizing Disney's complex and comprehensive modernism that we gain new insight into the corporation's Latin Americanism. For there's a resonance with the modernist impulses that seemed to course through a country such as Brazil at the time, visually represented by the famous patterns woven into Rio's sidewalks that feature prominently in the Latin sequence here, "Blame it on the Samba." And there's also an equally modernist fascination with the primitive, here the various African-influenced rhythmic instruments of Brazilian music.

"Blame it on the Samba" is a surreal portrayal of Donald Duck and his two avian compañeros Joe Carioca and the Mexican Panchito (first introduced in The Three Caballeros). Donald and Joe are feeling and (literally) looking blue. Panchito is a waiter at a restaurant "composed" of a musical score. To rejuvenate their spirits he mixes up a potent cocktail of Brazilian music: "You take a small cabassa (chi-chi-chi-chi-chi), One pandeiro (cha-cha-cha-cha-cha), Take the cuíca (boom-boom-boom-boom), You’ve got the fascinating rhythm of the samba." He then dunks his two guests in an enormous snifter, before diving in himself. Deep in the drink's murky depths is organist Ethel Smith, almost as extravagantly behatted as Carmen Miranda herself, who appears in live action combination with the antics of the suitably enlivened caballeros.

"Blame it on the Samba" is a surreal portrayal of Donald Duck and his two avian compañeros Joe Carioca and the Mexican Panchito (first introduced in The Three Caballeros). Donald and Joe are feeling and (literally) looking blue. Panchito is a waiter at a restaurant "composed" of a musical score. To rejuvenate their spirits he mixes up a potent cocktail of Brazilian music: "You take a small cabassa (chi-chi-chi-chi-chi), One pandeiro (cha-cha-cha-cha-cha), Take the cuíca (boom-boom-boom-boom), You’ve got the fascinating rhythm of the samba." He then dunks his two guests in an enormous snifter, before diving in himself. Deep in the drink's murky depths is organist Ethel Smith, almost as extravagantly behatted as Carmen Miranda herself, who appears in live action combination with the antics of the suitably enlivened caballeros. Things get really odd when Panchito takes a stick of dynamite to this underwater (undercocktail?) musical scene. The organ explodes, though Ethel continues playing none-the-less. It's as though she hasn't noticed that Disney has turned everything upside-down; that especially with its explosive Latin cocktails (one part mass culture, another part avant garde experimentation, a third part primitivism), Disney undoes any sense of familiar continuities. But the band plays on regardless.

Things get really odd when Panchito takes a stick of dynamite to this underwater (undercocktail?) musical scene. The organ explodes, though Ethel continues playing none-the-less. It's as though she hasn't noticed that Disney has turned everything upside-down; that especially with its explosive Latin cocktails (one part mass culture, another part avant garde experimentation, a third part primitivism), Disney undoes any sense of familiar continuities. But the band plays on regardless. YouTube Link: the entire "Blame it on the Samba" sequence. (Hat-tip: Latin Baby.)