¡Que Viva México!

It's only fitting that ¡Que Viva México! should be incomplete, fragmentary, subject to competing claims to ownership and reconstruction.

It's only fitting that ¡Que Viva México! should be incomplete, fragmentary, subject to competing claims to ownership and reconstruction.Chris Dashiell notes, in his long and informative article "Eisenstein's Mexican Dream", that "the film, like the pyramid at Chichen Itza" with which it opens, "is a ruin."

It's an artefact from a lost time when state communism was still the object of curiosity and even celebration among Western artists and intellectuals. It's also the residue of modernist fascination with Mexico, a country in which the surreal could be portrayed as everyday reality, and where time was out of joint: both the repository of age-old, unchanging primal imagery, and the location of the Americas' newest, most revolutionary impulses.

Latin America has always been caught within this double temporality and has often been cast as a universal unconscious. But Mexico in the period 1920-1940 incarnated these fantasies in peculiarly vivid fashion.

Moreover, the West's imagination of Mexico at this time resonated with and was magnified by the international success of the muralists José Orozco, David Siqueiros and, above all, Diego Rivera. Rivera (and his wife Frida Kahlo) hosted visiting luminaries such as André Breton, and befriended director Sergei Eisenstein. More importantly, the muralists' work served as the filter through which left-leaning intellectuals viewed Mexican society and history, leading them to think on epic scale of narratives by which timeless indigenism gave birth to the historic event of revolution.

And essentially this is the story that ¡Que Viva México! tells, of the Mexican people's slow but sure entry into history. The fact, however, that the crucial "Soldadera" section, in which the peasantry would be portrayed as finally agents of their own history, should be the section that was left unfilmed, could be read as a symptom of the ways in which that image of subaltern agency was multiply overcoded and orchestrated by the state on the one hand, and an international elite on the other.

What remains of Eisenstein's film, as repeatedly reconstructed (most fully to date in Grigori Aleksandrov's 1979 Soviet version), is a rather awkward hybrid of a study in visual form and an exercise in dramatic narration.

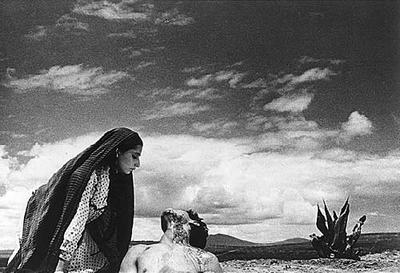

The Prologue, for instance, is a beautiful meditation on atemporality and ahistoricity, in which the indigenous are literally monumentalized, objectified as at one both with nature and with the ruins and carvings of Mayan civilization. The bullfight sequence in the "Fiesta" section, by contrast, is, as Dashiell rightly observes, full of narrative commonplaces that structure the clichéd action banally in terms of filial devotion and romantic courtship. Meanwhile, the central "Maguey" sequence alternates fascination with the visual architecture of the Maguey plant (at the outset) and the hacienda (at the end), with interspersed action sequences reminiscent of a second-rate Western.

In short, the film is a strange, at times enthralling, but fundamentally unsatisfactory encounter between the Soviet avant-garde impulses of the director, the Hollywood and commercial imperatives guiding its backer Upton Sinclair, and the images of a revolutionary indigenism on which both converge.

Finally, as Gilles Deleuze quotes Fellini saying, "the film is over when the money runs out." Eisenstein went over budget, Sinclair couldn't raise any more cash, Stalin refused to buy up the footage shot, and the project languished, to become quite literally a museum piece, in the custody of New York's Museum of Modern Art.

And this vision of Latin America would also be packed away for a while, to be resurrected only by Latin Americans themselves in the Cinema Novo and "Third Cinema" of the late 1960s. But the would-be Orozcos, Siqueiroses, and Riveras of the revolutionary neo-avant-garde would come up against the same obstacles that frustrated Eisenstein: that cinema is an art that demands huge capitalization and unprecedented labour power. Perhaps it is only in the era of digital video that an Eisenstinian Latin America could make it to the screen.

Labels: eisenstein, money