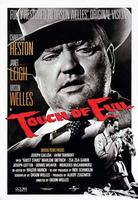

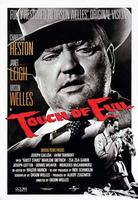

"This isn't the real Mexico. You know that." So says anti-narcotics cop Miguel Vargas to his new bride, Susie, in Orson Welles's

Touch of Evil.

Vargas, the senior cop who has just arrested one of the drug-running Grandi family in Mexico City, wants to clean up the reputation and image of his country, and so ensure that the place is safe for his young American wife. "I suppose," he says, "it would be nice for a man in my place to be able to think he could look after his own wife in his own country."

It turns out, though, that, the American motel in which Susie seeks refuge, "just for comfort," is a place of nightmarish danger: Janet Leigh here anticipates her performance in Hitchcock's

Psycho, as in this isolated and eerie motel her character is harassed, drugged, raped (metaphorically if not literally), and abducted by a gang of the younger Grandi family members. Over the course of the film, Susie endlessly crosses between the US and Mexico ("Across the border again?" she shrugs early on), but finds no respite either north or south.

For corruption and danger seep both sides of this porous border.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the film's famous opening long take. In its three and a half minutes, we see a bomb placed in a car outside a Mexican nightclub, which we then follow as its path entwines with that of the honeymooning couple Vargas and Susie. Camera, characters, and audience are drawn in this same uninterrupted sequence across the frontier to the US side. Alongside the raucous noise and music coming from cantinas and bars, alongside the brusque questions or idle chit-chat at the customs post, we hear the timer's tick-tock on the soundtrack, premonition of transborder violence that the guards will be unable to prevent.

Suddenly, the bomb explodes, bringing the film's first cut and tearing apart two mixed race couples: the car's occupants (an American businessman and Mexican stripper), instantly killed; and Vargas and Susie, their honeymoon peace shattered and a rift opened between national interests and private wellbeing. "This is going to be very bad for us," Vargas tells his wife. "For us?" she asks. "For Mexico, I mean," he replies.

But if Vargas starts out with a clear conception of his obligations and responsibilities to the nation, and an equally clear conception of their limits--regarding the US investigation of the bombing he declares himself to be "merely what the United Nations would call an observer"--as the film progresses this sense of a boundary between proper and improper soon becomes frayed and uncertain.

Increasingly desperate, searching for his wife on discovering her absence from the motel, he charges into a seedy dive and goes about the younger Grandi clan-members with his fists. "Listen, I'm no cop now. I'm a husband!" he shouts shortly before sending the bar crashing down.

Dishevelled and disorderly, driven by an anguished sense that his wife has been unjustly taken from him, Vargas has come to resemble his would-be nemesis, the corrupt US cop Hank Quinlan, played by Welles himself as a local hero now grotesquely gone to seed.

For thirty years Quinlan has been planting evidence to frame those he is convinced are guilty, after he had allowed his wife's killer, some "halfbreed," to go free. Ever since, he has been disgusted both with Mexicans and with "starry-eyed idealists. They're the ones making all the real trouble in the world." Vargas is Mexican and, at least at first, idealist: no wonder Quinlan should try to bring him down.

Quinlan's no hero: bloated, arrogant, and devious he personifies the state at its most corrupt. Vargas has to remind him that "the policeman's job is only easy in a police state. That's the whole point, captain. Who is the boss, the cop or the law?" The irony is that it should be Latin American chiding a US citizen about corruption and the dangers of dictatorship. But Quinlan's response poses a further irony: "Where's your wife, Vargas?" he asks, indicating his awareness that this macho Latin has failed to protect his woman. And Quinlan's intuition always seems to prove correct: in the film's closing moments, we learn that the man that he had tried to frame (another Mexican in a mixed relationship) has finally confessed to the crime of planting the bomb in what was his girlfriend's father's car.

Welles's vision is dark and unflinching. He allows us few certainties. This isn't the "real Mexico," and there's little pretence that Charlton Heston, playing Vargas, is a "real" Mexican: national identity and difference are presented as illusory; but these are illusions nurtured by the prejudice that drives almost every aspect of the film's plot. Even the otherwise innocent Susie displays a casual racism in nicknaming a Grandi minion "Pancho." "Why?" she is asked. "Just for laughs, I guess," is the best she can answer.

There's not much in this movie that's a laughing matter. Any attempt to save face or to present the law as other than a fundamentally dirty business is as self-defeating as Quinlan's final gesture, his attempt to wash his hands in the fetid rubbish-filled waters of the canal in which he finally dies. In the end, judgement is futile: Quinlan was "some kind of a man," as his former lover Tanya remarks, but "what does it matter what you say about people?"

Tanya (a remarkable cameo from Marlene Dietrich) is one of the few characters who retains self-control through the film. Tanya, whom we see calmly doing her accounts, a financial reckoning that abstracts from the desires and waywardness upon which her brothel thrives. "It's old, it's new," she says of the pianola installed in her parlour. "We got the television too."

And behind all the characters, often present somewhere within the frame, are the oil wells that like capital itself know no nationality. The oil wells, "pumping up money... money," that are the imperturbable, mechanical, inhuman backdrop to this tale of jealousy and prejudice, corruption and carnage, cross-border desire derailed.

Labels: orson welles, prejudice