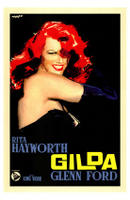

Gilda

Rita Hayworth had a good war, and was wrapped up in it "in a way no other movie icon was".

Rita Hayworth had a good war, and was wrapped up in it "in a way no other movie icon was". She was a favourite pin-up girl for US servicemen: One particular image, taken for the magazine Life, in which Hayworth kneels but also rises up from satin sheets, expectantly looking off camera, was second only to a bathing-suit picture of Betty Grable as GIs' choice to accompany them into battle. But where Grable was the girl next door, cheeky and charming, Hayworth radiated sensuality and a somewhat disturbing aura of power.

It was Hayworth's picture that adorned the first atomic bomb to be dropped on Bikini Atoll, a bomb nicknamed "Gilda."

Gilda is the role with which Hayworth is most associated: a sassy, seductive femme fatale in the noirish thriller that takes her name for its title.

Gilda is the role with which Hayworth is most associated: a sassy, seductive femme fatale in the noirish thriller that takes her name for its title. But Gilda herself hardly seems to have had such a good war as Hayworth: the film locates her, her husband the casino proprietor Ballin Mundson, and her ex-lover Mundson's right-hand man Johnny Farrell, all in Buenos Aires as the war ends.

Farrell appears first, taking money off US sailors by gambling with loaded dice. Mundson is in league with Nazis who (much as in Notorious) are using South America as their base for a sinister plot to take over the world. And Gilda? We know almost nothing about her past or what she is doing here so far from home.

The Buenos Aires that Gilda presents is a true noir landscape of smoke-filled, somewhat disreputable interior locations while outside is perpetual night and frequent rain. The film is set mostly in the illegal casino owned by Mundson and run by Farrell, its associated restaurant and dancefloor, or Mundsen's nearby mansion. The vitality and possibilities enshrined in these seedy but opulent locales appear at first as a welcome respite from the dangers lurking elsewhere: in the opening scenes Mundson rescues Farrell from a hold-up down at the docks, and gives him a pass to this new lifestyle of money, smart dressing, power, and responsibility.

But it becomes clear that the casino is at best a gilded cage, not least for Gilda who is trapped first by Mundsen and then (when Mundsen disappears and she takes back her old flame to be a second--third? fourth?--husband) by Farrell. In voiceover, Johnny tells us "She didn't know then what was happening to her. She didn't know then that what she heard was the door closing on her own cage."

Gilda's only recourse is to take advantage of and subvert the men's gaze and its constricting surveillance, by performing their fear and fantasy of female power as provocatively and outrageously as she can.

Gilda displays and flaunts female sexuality, most famously in the "Put the Blame on Mame, Boys" scene in which Hayworth performs a "clothed striptease": in fact all she removes is one glove, but then a striptease is never about revelation, about surface and depth, or rather never about the revelation of femininity. What's revealed, instead, is the desire of the men watching, who rush up in response to the classic line that ends the routine: "I'm not very good at zippers, but maybe if I had some help."

Here Johnny intervenes, takes Gilda off the dancefloor, and slaps her at precisely the point where she might otherwise reveal something of her history, the reasons that have led her to Argentina: "Now they all know what I am, and that should make you happy, Johnny. It's no use just you knowing it, Johnny. Now they all know that the mighty Johnny Farrell got taken, and that he married a..."

Through Gilda, the film consistently incites but also questions Johnny's power, and the power of the heterosexual male gaze. It suggests that Gilda's crime is to have broken up Johnny and Ballin's homosocial, perhaps even homosexual, relationship, which had been cemented around their mutual "friendship" for the phallic cane-cum-dagger that is Mundsen's signature prop, and around an agreement that women ("funny little creatures," Mundsen calls them) and gambling don't mix.

In the end, the sophisticated surveillance and insulation devices on which both Farrell and Mundsen depend are shown to fail. Both believe in setting up boundaries that they think they can make permeable or impermeable at will: their casino control room is an isolated eyrie in which business can be discussed, but also rigged with a series of electronic listening devices and shuttered windows through which they can observe what goes on around them. Mundsen believes in shutting the outside out at whim: "See how easily one can shut away excitement? Just by closing a window." But both characters are blinded by their gaze, deafened by their hearing.

Is this not because they remain fundamentally out of place? These American men believe that they can impose their own topography of power on Buenos Aires. But it's the two Argentine characters, who are constantly in the background, who permeate and belong to that background, who finally demonstrate that only they are fully aware of events. The lowly, philosophical bathroom attendant, Uncle Pio, hears all the casino gossip. It is Pio who kills Mundsen, the man who would rule the world, with his own best "friend," the blade emerging from its cane sheath. And ultimately the nondescript policeman, Detective Obregón, both gets his man and determines the fate of the other characters.

Gilda turns away: she can no longer bear to see or be seen. Her final words, the film's final words, are a plea to return to a more familiar world, a world in which she can become anonymous once again, can stop performing: "Johnny, let's go home. Let's go home."

Labels: performativity, rita hayworth