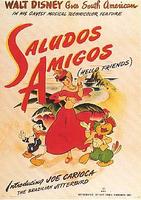

Saludos Amigos

Saludos Amigos, sponsored by Nelson Rockefeller's Office of Inter-American Affairs, presents us with a "good-will tour" of Latin America, undertaken by Walt Disney and his animators. As the accompanying documentary, South of the Border with Disney, puts it, "the visit resulted in a better understanding of the art, music, folklore and humor of our Latin American friends and a wealth of material for future cartoon subjects."

Saludos Amigos, sponsored by Nelson Rockefeller's Office of Inter-American Affairs, presents us with a "good-will tour" of Latin America, undertaken by Walt Disney and his animators. As the accompanying documentary, South of the Border with Disney, puts it, "the visit resulted in a better understanding of the art, music, folklore and humor of our Latin American friends and a wealth of material for future cartoon subjects." And indeed, the film features the debut of the Brazilian parrot character Joe Carioca, who would reappear in The Three Caballeros and go on to star in many, very profitable, Disney cartoons and strips made specifically for the Latin American market.

But it's not immediately clear what exactly Disney and co. may have given to their Latin friends in return, beyond innumerable sketches of Pluto (a particular favourite in Chile, we are told) and a rather disturbing regard for Gertulio Vargas's ability to choreograph massed ranks of singing children in Brazilian football stadia.

Meanwhile, the movie itself is a hybrid that combines travelogue, as the Disney party searches for "picture ideas" in the cultures and civilizations of Latin America, and four animated sequences, results of their search: Donald Duck as tourist in the Andes; a tale of Pedro the little Chilean mail plane; Goofy as Argentine gaucho; and Donald (again) meeting up with Carioca to explore Rio's sights and sounds.

In keeping with its documentary ethos, many of the film's drawings and images have a pseudo-scientific air; one is reminded of figures such as Humboldt and so eighteenth and nineteenth-century scientific illustrations of the new and strange flora and fauna encountered in voyages of discovery and exploration. Orchids, lilies, tapirs, Patagonian rabbits, and so on are presented and recorded in all their strange difference.

But this exoticism is tamed and made familiar as it is animated and integrated into Disney's own pre-existing narratives and cast of cartoon characters. For the wildlife are, equally, discussed as though they were candidates in a Hollywood screen test: Disney is searching for characters who can dance, play, sing, and interact with his established (and trademark) stars of Pluto, Donald, and so on.

But this exoticism is tamed and made familiar as it is animated and integrated into Disney's own pre-existing narratives and cast of cartoon characters. For the wildlife are, equally, discussed as though they were candidates in a Hollywood screen test: Disney is searching for characters who can dance, play, sing, and interact with his established (and trademark) stars of Pluto, Donald, and so on. Disney goes Latin (as Donald takes up an Andean pipe or plies a balsawood craft on Lake Titicaca) only to the extent that, and on the condition that, Latins (a llama or a Brazilian parrot) can go Disney. Here's the exchange implicit in good neighbourliness: Latin America is to open itself up as a market for US cultural exports, and in return, well, in return the North will give legitimacy to some of the region's less savoury regimes.

Labels: disney, geopolitics