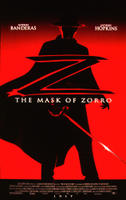

The Mask of Zorro

The Zorrathon continues. In The Mask of Zorro, Anthony Hopkins, Antonio Banderas, and Catherine Zeta-Jones revive the character for the era of the summer blockbuster; they also resuscitate the values with which the Zorro series had been associated, applying them to our contempory era of national insecurity.

The Zorrathon continues. In The Mask of Zorro, Anthony Hopkins, Antonio Banderas, and Catherine Zeta-Jones revive the character for the era of the summer blockbuster; they also resuscitate the values with which the Zorro series had been associated, applying them to our contempory era of national insecurity.Or rather, what they revive is a son-in-law of Zorro, less high class than the original. Which is pretty much the relationship between this film and the versions of the story that precede it.

Hopkins plays Don Diego de la Vega, and we see him at the outset as Zorro in his last hurrah, ridding California of Rafael Montero, the corrupt Spanish governor, before preparing for retirement with his wife and newborn baby. But his plans are interrupted as the governor turns up at his hacienda, his wife is killed, his child taken from him, his property burned to the ground, and he himself is taken away to rot forgotten in a dank prison cell.

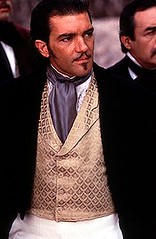

Until twenty years later... when Montero returns with dastardly ambitions to wrest California from the Mexicans, Don Diego escapes from his dungeon, and Alejandro Murrieta (played by Banderas) is trained up to assume the mantle of Zorro and so to avenge both Don Diego and his own murdered brother. Zeta-Jones, meanwhile, is Don Diego's now grown-up daughter, raised by Montero as his own, and soon to seduce and be seduced by the dashing Alejandro.

By the dashing Alejandro, that is, because unlike previous Zorro incarnations here Zorro himself is no aristocrat. Murrieta has to be taught charm by his older mentor; but he is taught so well that he passes perfectly for a young gallant and so wins Montero's trust (and learns of his dastardly plan). Indeed, in a reversal of the pattern established by Douglas Fairbanks and continued by both Tyrone Power and Alain Delon, Banderas as bandit raises more laughs than does Banderas as beau. He is even, if anything, less accomplished as bandit: late on in the movie, he is still falling off his horse in a series of comic pratfalls.

By the dashing Alejandro, that is, because unlike previous Zorro incarnations here Zorro himself is no aristocrat. Murrieta has to be taught charm by his older mentor; but he is taught so well that he passes perfectly for a young gallant and so wins Montero's trust (and learns of his dastardly plan). Indeed, in a reversal of the pattern established by Douglas Fairbanks and continued by both Tyrone Power and Alain Delon, Banderas as bandit raises more laughs than does Banderas as beau. He is even, if anything, less accomplished as bandit: late on in the movie, he is still falling off his horse in a series of comic pratfalls.So in the transition from older to younger Zorro, honour is universalized (the poor too have their honour) and class relativized (anyone can be taught taste). No longer is Zorro's aim, as it was in 1920 and 1940, to rally his fellow blue-bloods against colonial tyranny. Rather it is his nemesis who is the usurper, and our hero is fighting to preserve national unity by preventing the country's disintegration, and to serve the state whose assets Montero is plundering.

This is, in short, the first postcolonial Zorro: postcolonial not simply because it takes place after Mexican independence has been achieved, nor even just because it foregrounds subaltern mimicry, but also because its theme is the populist cross-class alliance to consolidate national identity.

It is also perhaps the first pop culture Zorro. Though, as I've commented before, in many ways Zorro is the model for future superheroes such as Batman and superman, here the Zorro story is itself in turn influenced by, for instance, the Bond franchise (which provides the scheming and megalomaniac villain) and Star Wars (which gives us the mentor instructing his pupil in the way of good combat and good conduct). The movie is a homage not only to previous iterations of the Californian crusader, but also to the whole gamut of wholesome swashbuckling and cheeky anti-authoritarianism that marked so much of Hollywood production across the twentieth century.

Latin America becomes the setting within which US popular culture can rediscover the best and most uplifting elements of its heritage. This 1998 Zorro is self-consciously a throwback, to Saturday matinées and violence without gore, in fact with remarkably few fatalities. Is not the fear of a fragmented postcolonial nation not a fear felt acutely in the US at the turn of the century? Neither anti-communism nor shared prosperity, Hollywood's great post-war unifiers, can mask an increasing sense of political division and cultural balkanization.

The year this movie came out was, after all, also the year in which the Lewinsky scandal broke and political battle lines between liberals and (neo)conservatives were more spectacularly on display than at any time since the Vietnam war.

The year this movie came out was, after all, also the year in which the Lewinsky scandal broke and political battle lines between liberals and (neo)conservatives were more spectacularly on display than at any time since the Vietnam war. And that same year was the year that the US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya were bombed, by the then little-known al-Qaida network, and so an early premonition of what would become the war against terror.

So, if postcolonial texts are always (as Fredric Jameson suggests) national allegories, what better vehicle to allegorize Hollywood's power to bind together a nation starting to fall apart than a feel-good return to 1940s values displaced to a pop-culture inflected postcolonial Latin setting?

Labels: postcolonialism, zorro