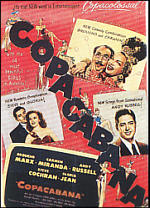

Copacabana

It's no great surprise that latinidad can be and often is a matter of performance. Indeed, it was Carmen Miranda, Portuguese-born, Brazilian-raised, US-domiciled, who had established the model for Latin performance in the early and mid-1940s.

It's no great surprise that latinidad can be and often is a matter of performance. Indeed, it was Carmen Miranda, Portuguese-born, Brazilian-raised, US-domiciled, who had established the model for Latin performance in the early and mid-1940s. But in Copacabana, seven years after her Hollywood debut in Down Argentine Way, Miranda tries to shake off her image, show that she can perform European, act as well as sing, and veil the "Brazilian bombshell" reputation that was leading her career nowhere.

The film's plot has Groucho Marx as Lionel Q. Devereaux who, with Miranda's Carmen Navarro, is one half of a down-at-heel double act unable to get bookings. Frustrated, Devereaux turns agent and by mischance books Navarro at the Copacabana club twice: once as herself, a South American cha-cha girl, and again as blonde French chanteuse Mademoiselle Fifi. Naturally, this double identity has to be concealed from the club owner Steve Hunt and the ever more curious press. But the duplicity becomes unmanageable as Hunt falls for Fifi and press attention brings Hollywood movie producers to town.

Mademoiselle Fifi, in short, soon eclipses Navarro, who from the start is portrayed as but one more in a line of what have become seen as Latin novelty acts. "I've got sixteen of them on my list," says talent agent Liggett of South American singers, "they're a dime a dozen."

Mademoiselle Fifi, in short, soon eclipses Navarro, who from the start is portrayed as but one more in a line of what have become seen as Latin novelty acts. "I've got sixteen of them on my list," says talent agent Liggett of South American singers, "they're a dime a dozen." As the consequences of her performance become evident, Carmen-as-Fifi tries to deflect attention back to Carmen-as-Carmen, but no dice: latinidad is no longer saleable, and it's Fifi's contract alone that becomes subject to an increasingly inflationary bidding war.

In the end, the blonde chanteuse has to be killed off, but the police are called in as Devereaux's disposal of his former star is taken a little too literally. Carmen therefore has once more to veil herself and play French, but this time in order that she be unmasked as "really" Navarro. Even with her veil off, however, doubt remains, which Carmen can only dispel by kissing Hunt (and the various other male characters). For only Carmen, it turns out, can kiss like Fifi.

The final twist (if one can really talk of twists in such a thoroughly predictable movie) is that the whole story is taken up, self-reflexively, to become the plot of a movie to be entitled... Copacabana.

It would seem, therefore, that here almost everything is on the surface: Miranda's own declining appeal, her inability to break out of the mold that she herself helped shape, the limits set to performativity by Hollywood's economic realities. But almost un-noticed, the film subtly indicates another story, of successful whitening.

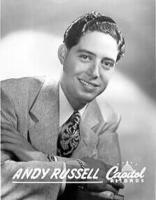

Andy Russell plays (a version of) himself as the Copacabana's male star. Russell is presented as all looks and voice and no brain, a clean-cut kid continually befuddled by what's going on around him.

Andy Russell plays (a version of) himself as the Copacabana's male star. Russell is presented as all looks and voice and no brain, a clean-cut kid continually befuddled by what's going on around him. Yet Andres Rabajos (as this Chicano vocalist was born) was no doubt more aware than anyone of the dangers and possibilities of Anglicization as a strategy to make it in the USA. A crooner in the style of Bing Crosby and Russ Columbo, Russell's first hits had been Spanish language ("Bésame mucho" and "Amor"), but he crossed over and by the later 1940s had become arguably "the first truly successful Latino-American vocalist".

By the 1950s, Russell's star, like that of Miranda, was on the wane, and he moved to first Mexico then Argentina. But his apparently unquestioned all-Americanness in Copacabana is a reminder that for many--from Rita Hayworth (born Margarita Cancino) to Anthony Quinn (Antonio Rudolfo Oaxaca Quinn)--success could come for Latinos playing gringo.

See also: That Night in Rio, Week-End in Havana, The Gang's All Here, Carmen Miranda.

Labels: carmen miranda, performativity