The Gaucho

The original programme notes to The Gaucho, while emphasizing the painstaking research that lies behind the film's script and scenography, state that:

The original programme notes to The Gaucho, while emphasizing the painstaking research that lies behind the film's script and scenography, state that:Douglas [Fairbanks] has always held that "things as they are" are never as appealing as "things as we would like to see them."But what then does this film indicate about what its audience would like to see?

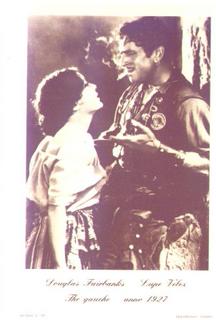

The answer would appear to be: miracles, shrines, macho Argentine country-folk, Lupe Velez's heaving bosom, and the power of religion to redeem even the most inveterate of criminals.

Meanwhile, we would like to see gauchos, if Douglas Fairbanks's portrayal is anything to go by, as raucous, rambunctious folk, who like to drink, dance, and fight, are athletic and a hit with the ladies, and who smoke like a chimney. Fairbanks's cigarette is his constant prop. At one point he swallows it up within his mouth while he pauses to kiss Velez, the mountain girl, only for it to pop out again shortly afterwards.

As always, however, the gauchos are a dying breed. (And it ain't just the lung cancer that'll get 'em.)

Though this film portrays them at their peak, overwhelming Andean villages and evil dictatorial usurpers alike, it also shows the gaucho tamed. Struck by a dreaded lurgy (the "black doom"), a mysterious illness that makes his hand black and numb, Fairbanks's un-named gaucho is about to commit suicide until the saintly girl of the shrine leads him to where Mary Pickford (playing the Virgin Mary) can cure him and turn his life around. Converted to Christianity, he determines to make an honest woman of his lover, Velez, and so presumably an honest, no longer gaucho, man of himself.

The Gaucho was touted for its lavish and expansive sets. The Andes here are near vertical cliffs, within which the people live in no more than caves. The plains, on the other hand, are bedecked with palm trees and throng with cattle for as far as the eye can see.

But who tends these cattle? Hardly anyone here works. Aside from the bartender in the village cantina and the padre at the shrine, the people are divided into three roughly equal parts: beggars, soldiers, and bandits.

This is a story set in some mythical, premodern past. The Latin America presented here is almost entirely a generic image of rural poverty, militaristic tyranny, and popular religiosity, The gaucho bolas, horsemanship, and spurs are the particularistic details around which the shallow characterization is spun. But everything blurs in a haze of cigarette smoke and the dust raised by stampeding cattle.