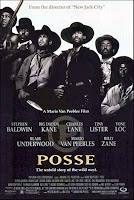

Posse

Mario Van Peebles's Posse sets out to re-envision the making of the US West, and so also a central aspect of the country's mythological history. The film's claim is that African Americans were central to the movement west: that up to a third of cowboys were black, and for instance also that Los Angeles was a majority black town at its foundation. Moreover, with its street-smart beat and stars such as Isaac Hayes and Big Daddy Kane, the movie wants to draw a direct lineage between the posses of the wild west and the posses of the contemporary urban metropolis.

Mario Van Peebles's Posse sets out to re-envision the making of the US West, and so also a central aspect of the country's mythological history. The film's claim is that African Americans were central to the movement west: that up to a third of cowboys were black, and for instance also that Los Angeles was a majority black town at its foundation. Moreover, with its street-smart beat and stars such as Isaac Hayes and Big Daddy Kane, the movie wants to draw a direct lineage between the posses of the wild west and the posses of the contemporary urban metropolis.But the film starts in the Cuban-American war of 1898. Here we meet the movie's protagonist, Jesse Lee (played by Van Peebles himself), and its antagonist, Colonel Graham (Billy Zane). Graham commands Lee and a rag-tag of other mostly black soldiers to undertake a secret mission, in civvies, to intercept a Spanish supply convoy and grab whatever arms and ammunition may be available. But the real object of the raid is gold, and Graham's aim is to frame the men for desertion and then to disappear with the loot. A shoot-out ensues, in which Lee shoots Graham's eye out, and those that survive of Lee's troop become mutineers for real, scarpering off to the mainland to become the film's eponymous posse. Soon they find, however, that the Colonel has raised a posse of his own, and is set on tracking them down, to demand his bullion back, and to seek an eye (or more) for an eye.

This plot overlaps with and is in some tension with another, in which Jesse melts down some of his gold into bullets, for it is only with such precious armament that he can put an end to the demons that haunt him from his past. He sets out West, to the site of a utopian black community founded by his father on peaceful, non-violent lines, but which the elder Lee never got to see as he was brought down and killed by vengeful white vigilantes. One by one these tormentors from the past are dispatched by Jesse's deadly sharp-shooting, and in the process he persuades the community of Freemanville that sometimes it's no crime to stand up for your rights with a show of force. In the middle of the final gun-battle, one character is seen asking "Why can't be just get along?" in an ironic echo of Rodney King's plaint in the context of contemporary white vigilantism. But the entire film is designed to show the myriad reasons why such liberalism is a dead-end for the cause of African American justice.

The film's major contradiction is that it is, well, just a film, and as such its politics consists in the liberal gesture of representation and revisionism. Its charge is that Hollywood has whitened the image of the West, erasing the African American presence from the frontier. In so far as Posse aims to put black faces back in the frame, and for all its representational shock tactics (easily absorbed by the MTV generation, however), it's no more, if no less, than an extension of Black History month.

The film's narrative contradiction, on the other hand, concerns the uneasy interplay between its two plots: the Cuban-American "Buffalo Soldiers" on the one hand, and the lone avenger of the father's shattered dream, on the other. A sign of this tension is the fact that Lee is repeatedly separated from his posse. For his gang is in fact an inter-racial assemblage, forged in the realization that foreign wars such as the intervention on Cuban soil have less to do with liberty than with plunder and the continued exploitation of the US color line. The posse itself, in short, has more to do with class; it is Lee's personal battle with his truncated inheritance that revolves around race.

The film's narrative contradiction, on the other hand, concerns the uneasy interplay between its two plots: the Cuban-American "Buffalo Soldiers" on the one hand, and the lone avenger of the father's shattered dream, on the other. A sign of this tension is the fact that Lee is repeatedly separated from his posse. For his gang is in fact an inter-racial assemblage, forged in the realization that foreign wars such as the intervention on Cuban soil have less to do with liberty than with plunder and the continued exploitation of the US color line. The posse itself, in short, has more to do with class; it is Lee's personal battle with his truncated inheritance that revolves around race.There's an attempt to bring the two plotlines together: first when the posse rallies round to defend Freemanville, and it is the group's white character who becomes the sacrificial victim for Anglo rage; and second when it turns out that the community's black mayor cares more about money than about solidarity, and is prepared to sell the communal land when the railroad nears and raises property prices. Accordingly he, too, has to die, albeit at white hands rather than black, leaving Jesse racially pure if still uncertain about class.

But the final encounter is with the Colonel, and the principle that the last battle is the most significant suggests that it's the Cuban-American trauma rather than the collapse of frontier utopianism that most marks Jesse's fate. Perhaps Van Peebles is never quite idealistic enough to believe that the failure of non-violent communalism is such a disaster. Still, the fact that he casts his own father in the film, as well as a host of stars from the past, not least the veteran black actor Woody Stode who relates the entire tale as though in flashback, suggests that the director himself can't quite make up his mind about this inheritance of attempts to work within rather than without the system.

YouTube Link: Intelligent Hoodlum, "The Posse (Shoot 'Em Up)".