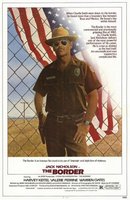

The Border

It's no surprise to learn that Bruce Springsteen is a fan of Tony Richardson's The Border. This film's emotional tone is very much the understated disgust and despair characteristic of Springsteen songs such as "The Line" or "State Trooper"; indeed, "The Line" is said to have been inspired by the movie.

It's no surprise to learn that Bruce Springsteen is a fan of Tony Richardson's The Border. This film's emotional tone is very much the understated disgust and despair characteristic of Springsteen songs such as "The Line" or "State Trooper"; indeed, "The Line" is said to have been inspired by the movie.For Richardson as much as for Springsteen, the border between the US and Mexico points up a series of divisions that are in fact internal to the USA. And all of these borders provoke anxiety because they are so permeable and unfixed.

There is the US's institutional hypocrisy: the state throws resources at keeping Latin American immigrants out, and yet the economy of the South West would collapse were it not for this cheap labour willing to take on work that white Americans regard as beneath them. Caught in this contradiction, the corruption that this movie portrays as endemic to the border patrol is inevitable. The patrolmen know better than anyone that their task is both counter-productive and impossible, as they continually send the same people back again and again, only postponing their successful crossing, so drawing out their suffering in the meantime.

Then there is the fact that these migrants are simply taking the American Dream at its word. The Border hardly has a sanguine view of the pursuit of happiness through consumer goods or social distinction. But it shows that white Americans who want no more (and no less) than a new condo, with pool in the garden and waterbed in the bedroom, have little solid ground from which to criticize Latin Americans who come north similarly seeking material benefit. (Charles Taylor's "The Broken Promised Land" focusses on this aspect of the film.)

Finally, there is the line that border agent Charlie Smith (magnificently played by Jack Nicholson) literally draws in the sand: his is an attempt to stake out a limit, a personal code of ethics in the midst of the contradictions and corruption that surrounds him. His limit is a refusal to condone his patrol buddy's extrajudicial killings. "You see this line?" shouts Charlie. "That's as far as I go! No murders!" "Okay," replies Cat (Harvey Keitel), "I can respect that."

Finally, there is the line that border agent Charlie Smith (magnificently played by Jack Nicholson) literally draws in the sand: his is an attempt to stake out a limit, a personal code of ethics in the midst of the contradictions and corruption that surrounds him. His limit is a refusal to condone his patrol buddy's extrajudicial killings. "You see this line?" shouts Charlie. "That's as far as I go! No murders!" "Okay," replies Cat (Harvey Keitel), "I can respect that."But on the border the law no longer makes sense, and the film shows both that Cat can provide some rationale for killing drug-runners but letting other immigrants through for a profit, and that Charlie too eventually takes life and death into his hands in an effort to enforce his own code of honour.

The border is a zone of exception in which the law is suspended, and what Giorgio Agamben terms force-of-

Perhaps the greatest irony comes when the border police chief tries to explain to the boss of the coyote people-smuggling operation why a truck full of migrants has been stopped: it's been chased down by a couple of honest border guards and "Goddamit, I ain't got no control over that! That's just gonna happen sometimes."

Meanwhile, Charlie's doubts and moral uncertainty are played out over and around the figures of three Guatemalan refugees: a brother and sister, plus the sister's little baby, who leave their village after an earthquake in the movie's opening scene. Charlie sees the sister from across the Rio Grande while the brother is on the US side, stealing his car's hubcaps. From that point on he gradually becomes obsessed by the trio's fate, saving the brother from the wheels of a freight train, and trying to save the sister from prostitution in a seedy strip joint in the Mexican border town. When the child is stolen (to be sold for adoption to a rich white family), Charlie makes it his mission to recover and return him to his mother.

To all intents and purposes, this young woman is essentially mute: she speaks no English and is given only a few lines of (untranslated) dialogue in Spanish. She's a near perfect subaltern. (Interestingly, the same actress, Elpidia Carrillo, plays a very similar part in Oliver Stone's Salvador.)

And when Charlie tries to explain why he has become so obsessed with her salvation, the best he can come up with is that "I wanna feel good about something sometime."

But Charlie fails to get this group over to the US. He fails even to ensure that they all survive through to the film's final frame. The best he can manage is a kind of second-order compensatory restitution, effected in the middle of the Rio Grande, in the shadow of the transborder bridge and US flag in the background.

In the end, this physical frontier, no more than a dirty stream, is the least substantial of any of the borders featured in Richardson's film. The Border can only gesture towards larger, systemic issues, in the face of which it suggests revenge is feeble and reconciliation fleeting.

And perhaps this is the film's grandeur: that it is an "issue" movie without even pretending to offer resolution.

Labels: border, contradiction