Raiders of the Lost Ark

Though the bulk of Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark is set in Egypt, in its opening shot the trademark Paramount logo fades into the silhouette of an Andean mountain that bears more than a passing resemblance to Huayna Picchu, the peak that towers over the Peruvian archaeological site of Machu Picchu. And in the vignette that establishes Indiana Jones's character and role (and so the three-film series that is to follow), we are firmly in Latin America.

This opening sequence, like the similar openings to Bond films, is at best peripherally related to the film's main plot. The derring-do archaeologist Jones is in search of a golden idol hidden within what appear (judging by the characteristic stonework) to be Inca ruins. He faces innumerable dangers: hostile Indians, the "Hovitos," who seem to have emerged from the Amazon basin along with their blowpipes and poison-tipped darts; a series of arcane booby traps left presumably by the Incas themselves; and finally, a hostile competitor, the Frenchman René Belloq, who later (in the pay of the Nazis) reappears once again as Jones's would-be nemesis, a "shadowy mirror image" of Jones himself.

The film thus sets up a series of mythic archetypes. There is the archaeologist as adventure hero, combining scientific discovery with an unorthodox policing of the past and its legacy. There is Inca civilization itself as a trap-filled labyrinth of almost unrivalled ingenuity, employing its knowledge and expertise to protect itself in the future even long after its own cultural extinction. There is Latin America as an anything-goes playground in the "great game" of inter-war imperial rivalry. And then there is an image of the 1930s as haven of family-friendly boys-own action narratives, providing cartoon escapades as a relief from the tedium of modernity and standardization.

As in Tintin's jaunts through Third World danger zones, the "Indiana Jones" series displaces the conflicts between the great powers of the 1930s onto a periphery (Lima, Katmandu, Cairo) of flying boats and headhunters, mummies and submarines. Technology meets prehistory, the two combining to create the romance and mystique of early twentieth-century modernity.

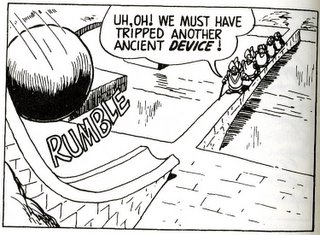

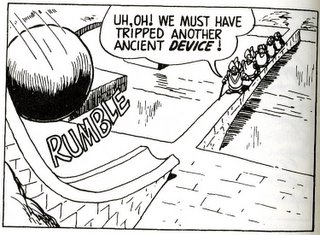

Somewhat ironically, however, as Cal Meacham notes at some length, the model for this episode in Raiders of the Lost Ark would appear to be neither Tintin nor, say, Flash Gordon, but the rather less than heroic adventures of Donald Duck, as drawn by Carl Barks. Specifically, the referent here consists of two 1950s strips: "The Seven Cities of Cibola" and "The Prize of Pizarro," in which Uncle Scrooge, Donald, and the young Duck nephews search for gold relics and dodge multiple obstacles, including a giant stone ball.

Is more evidence needed that the "ark" that Hollywood repeatedly raids is less the resource that realism could offer than its own pop culture archive of protean, self-generating myth?

As Geoffrey Blum puts it in "Wind from a Dead Galleon":

This opening sequence, like the similar openings to Bond films, is at best peripherally related to the film's main plot. The derring-do archaeologist Jones is in search of a golden idol hidden within what appear (judging by the characteristic stonework) to be Inca ruins. He faces innumerable dangers: hostile Indians, the "Hovitos," who seem to have emerged from the Amazon basin along with their blowpipes and poison-tipped darts; a series of arcane booby traps left presumably by the Incas themselves; and finally, a hostile competitor, the Frenchman René Belloq, who later (in the pay of the Nazis) reappears once again as Jones's would-be nemesis, a "shadowy mirror image" of Jones himself.

The film thus sets up a series of mythic archetypes. There is the archaeologist as adventure hero, combining scientific discovery with an unorthodox policing of the past and its legacy. There is Inca civilization itself as a trap-filled labyrinth of almost unrivalled ingenuity, employing its knowledge and expertise to protect itself in the future even long after its own cultural extinction. There is Latin America as an anything-goes playground in the "great game" of inter-war imperial rivalry. And then there is an image of the 1930s as haven of family-friendly boys-own action narratives, providing cartoon escapades as a relief from the tedium of modernity and standardization.

As in Tintin's jaunts through Third World danger zones, the "Indiana Jones" series displaces the conflicts between the great powers of the 1930s onto a periphery (Lima, Katmandu, Cairo) of flying boats and headhunters, mummies and submarines. Technology meets prehistory, the two combining to create the romance and mystique of early twentieth-century modernity.

Somewhat ironically, however, as Cal Meacham notes at some length, the model for this episode in Raiders of the Lost Ark would appear to be neither Tintin nor, say, Flash Gordon, but the rather less than heroic adventures of Donald Duck, as drawn by Carl Barks. Specifically, the referent here consists of two 1950s strips: "The Seven Cities of Cibola" and "The Prize of Pizarro," in which Uncle Scrooge, Donald, and the young Duck nephews search for gold relics and dodge multiple obstacles, including a giant stone ball.

Is more evidence needed that the "ark" that Hollywood repeatedly raids is less the resource that realism could offer than its own pop culture archive of protean, self-generating myth?

As Geoffrey Blum puts it in "Wind from a Dead Galleon":

Raiders was a foregone conclusion the minute Lucas and Spielberg saw Barks' emerald idol--the one false bit of archaeology in an otherwise superbly researched story. For them it didn't matter. That statue crystallized all the thrills of pulp fiction into one shining image which eventually gave birth to three Indiana Jones epics.Again, then, we see the power of that particular mythic formulation that is Hollywood's Latin America. Though to describe it as mythic is hardly to downplay its potential to induce real effects--as Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart's How to Read Donald Duck would be among the first to remind us.