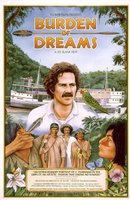

Burden of Dreams

Do not listen to the analysts. Do not listen to the Freudians or any of those bozos. I am a person who does not dream. (Herzog, in Dreams and Burdens)The Criterion DVD edition of Burden of Dreams comes with a wealth of material that collectively combine as a kind of supplementary monument to Werner Herzog's Fitzcarraldo, but also as a series of supplements to that supplement: there is the documentary itself, filmed by Les Blank. There is a dual commentary track, by Blank and his sound recordist Maureen Gosling as well as by Herzog himself.

Then there is also an extended interview with Herzog, Dreams and Burdens, recorded in 2005. There are deleted scenes, even an additional documentary Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe. Finally, as though this cinematic material were not enough, there's a written essay, "In Dreams Begin Responsibilities," by Paul Arthur, and an eighty-page book with excerpts from the diaries of both Blank and Gosling.

Supplements upon supplements. As Herzog notes, he feels somewhat strange commenting on what is itself a comment upon his own film. What is it about Fitzcarraldo that demands so much further information, discussion, unpacking, and interpretation? Is all this not overkill for a film that, Herzog asserts, requires no analysis?

Yet in some ways, it is not enough. Herzog, Blank, and Gosling all point out how much is missing: the makers of Burden of Dreams were only in Peru, where Fitzcarraldo was shot, for two brief visits. They weren’t there, for instance, for the first five weeks of filming, when Jason Robards and Mick Jagger were still involved with the project. They weren’t there, either, at the end, when Herzog finally accomplished what their documentary shows him repeatedly failing to achieve: to drag his steamship over a mountain.

Even when Blank and Gosling were around, there were many times, Herzog repeatedly tells us, that Blank somehow missed important episodes. He overslept, he was looking the other way, he missed his chances. Blank himself reports that at one crucial point, as the steamship ricocheted down the “Pongo de la Muerte” rapids, he was clasping his camera to his chest rather than getting a shot of the impact in which Herzog’s cinematographer cut his hand open.

And of the footage that remains, Gosling reminds us that much was cut; so many sequences had to be discarded. Notably omitted is what for Herzog was clearly a major part of the experience shooting Fitzcarraldo: Klaus Kinski’s rages, including a sequence Blank shot which Herzog includes in My Best Fiend, relegated here to one of the “supplements,” a deleted scene excluded from the main story.

The suggestion is that Blank fails to portray the "real" of Fitzcarraldo, that Burden of Dreams can only be parasitic, secondary to the main event. But, as Paul Arthur's perceptive essay suggests, also at stake is a disagreement as to what constitutes that main event.

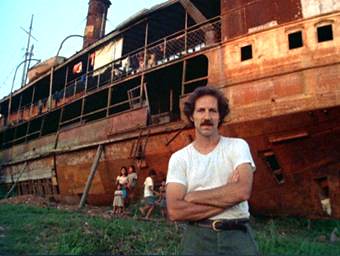

For Herzog, the story has always to be the heroic narrative of the individual battling his environment. It's in this sense that he as a director identifies so fully with the character Fitzcarraldo. Both struggle to impose their mastery on a jungle regarded as horrific, obscene, full of "fornication," "misery," and death.

For Blank, on the other hand, that construction of the jungle is too clearly a projection of Herzog's unconscious desires, of an unconscious almost fully externalized and mapped on to the what is around him. Herzog needs no introspection (he claims hardly to look into a mirror, and not to know even the colour of his own eyes) precisely because he has projected his psyche onto the world. That is Herzog's madness: to see all around only a test of his desire, his will, and his "guts." Everything (even, in Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe, his leather loafers) can be claimed and digested precisely because it is all only a figure for his own imagination, his own dreams.

As Arthur observes, however, although Blank allows Herzog to present his rather ponderous and melodramatic pronouncements on the Amazon jungle as irredeemably other, he demonstrates how this otherness is Herzog's own construction by "calmly cut[ting] away to images of picturesque flora and fauna, a clear contradiction of Herzog's nihilism."

Which is not to say that for Blank, Latin America is any the less "other." But whereas for Herzog, the Amazon is a threatening cancellation of his own identity, a figuration of the unconscious forces against which he must perpetually struggle, for Blank the rainforest has its own logics, both human and inhuman, that remain at best blithely indifferent to the film-maker's efforts.

While Herzog poses heroically in the foreground, behind his back other processes unfold of which he will remain forever ignorant.

Herzog envisages a cosmic psychomachia of man against environment. Blank presents singularities that form contingent associations (as the indigenous peoples temporarily put in their lot with the Western film-makers) but retain their own priorities, their own agendas set according to their own timescales and desires.

Indeed, for Burden of Dreams there is perhaps no main event: rather, a brief coincidence of Western and Latin American logics that engenders multiple events, each of which will take on greater or lesser significance depending upon the perspective from which they are viewed.

Labels: herzog, unconscious