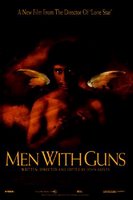

Men with Guns

The virtues of a road movie are that it can easily combine both realism and fantasy. On the one hand, as in a classic nineteenth-century novel, the episodic nature of road movies effortlessly shows us all the different estates and occupations that constitute society as a whole. On the other hand, few cinematic journeys are ever fully innocent: they soon acquire the character of a fable or mythical quest.

In Men with Guns, then, John Sayles takes on the road movie genre to show us a cross-section of an un-named contemporary Latin American country and to spin a fable of fantasies both utopian and touristic.

In Men with Guns, then, John Sayles takes on the road movie genre to show us a cross-section of an un-named contemporary Latin American country and to spin a fable of fantasies both utopian and touristic.

Physical geography reveals also human variation. As the film moves from the capital to the countryside, from the plains to the highlands, we also move from a world of bourgeois civility to campesinos eking out an increasingly precarious existence from salt-selling, cane-cutting, or coffee-picking.

The movie's protagonist is Dr Humberto Fuentes, a recently-widowed doctor and medical professor from the capital who is searching for his former students, whom he had sent out three years earlier on a health program to work with the country's indigenous peoples.

En route, he is joined by an orphaned campesino boy, an army deserter, a defrocked priest, and a young woman struck mute since her horrendous rape at the hands of the military.

For everywhere Fuentes goes he finds that the "men with guns" have been there before him. From the army officer in his well-appointed surgery at the film's outset, to the company of soldiers guarding a "model village" of displaced people in the highlands, to the guerrillas in the cloud forest, their influence is all-pervasive.

The quest, then, becomes the search for a place where there will be no more violence, a utopian space "where men with guns don't go" represented by the semi-mythical village "Cerca del Cielo" ("Close to Heaven") that people describe as somewhere "más adelante," "further on," and almost magically hidden from both the army and the guerrillas.

But the words that Fuentes uses to invoke Cerca del Cielo (as he convinces the young mute not to take her own life, not to give up on the quest) are taken straight from a tourist brochure advertising a resort somewhere near Bali: it's a place "where the air is like a caress, where gentle waters flow, where wings of peace lift the burdens from your shoulders."

For this utopian quest comes to overlap with the travels and travails of a pair of US tourists who are out searching for archaeological sites. The two journeys, the search for political refuge and the backpackers' trail, constantly intertwine: early on Fuentes meets the US couple in a roadside restaurant, where (still ignorant about his country) he tells them that accounts of army atrocities are fabrications of the foreign press; later we discover that the tourists are obsessed by a conception of a Latin American culture blood-soaked from an epoch of pre-Columbian sacrifice.

While both natives and foreigners are in some senses looking to turn back time, the tourists are overly fascinated with death, but Fuentes is trying to move past the violence that he's inadvertently uncovering to reach the oasis of peace that, ironically, the Western tourist industry has given him the language to describe.

Finally, this complex and perhaps almost unique film (made by a US director but mostly in Spanish and indigenous languages) maintains a delicate balance between the opposed conceptions of Latin America as utopia and as heart of darkness, between indigenous authenticity and globalized hybridity.

It ends ambivalently and uncertainly: Fuentes fails to find his students, but he does encounter both death and repose; Cerca del Cielo exists, but is no paradise, rather a place of what Sayles himself terms "quiet desperation." It's "where rumors go to die." Still, in its final shot, the film holds out the possibility of yet another más adelante, a continued dream of something better further on.

In Men with Guns, then, John Sayles takes on the road movie genre to show us a cross-section of an un-named contemporary Latin American country and to spin a fable of fantasies both utopian and touristic.

In Men with Guns, then, John Sayles takes on the road movie genre to show us a cross-section of an un-named contemporary Latin American country and to spin a fable of fantasies both utopian and touristic. Physical geography reveals also human variation. As the film moves from the capital to the countryside, from the plains to the highlands, we also move from a world of bourgeois civility to campesinos eking out an increasingly precarious existence from salt-selling, cane-cutting, or coffee-picking.

The movie's protagonist is Dr Humberto Fuentes, a recently-widowed doctor and medical professor from the capital who is searching for his former students, whom he had sent out three years earlier on a health program to work with the country's indigenous peoples.

En route, he is joined by an orphaned campesino boy, an army deserter, a defrocked priest, and a young woman struck mute since her horrendous rape at the hands of the military.

For everywhere Fuentes goes he finds that the "men with guns" have been there before him. From the army officer in his well-appointed surgery at the film's outset, to the company of soldiers guarding a "model village" of displaced people in the highlands, to the guerrillas in the cloud forest, their influence is all-pervasive.

The quest, then, becomes the search for a place where there will be no more violence, a utopian space "where men with guns don't go" represented by the semi-mythical village "Cerca del Cielo" ("Close to Heaven") that people describe as somewhere "más adelante," "further on," and almost magically hidden from both the army and the guerrillas.

But the words that Fuentes uses to invoke Cerca del Cielo (as he convinces the young mute not to take her own life, not to give up on the quest) are taken straight from a tourist brochure advertising a resort somewhere near Bali: it's a place "where the air is like a caress, where gentle waters flow, where wings of peace lift the burdens from your shoulders."

For this utopian quest comes to overlap with the travels and travails of a pair of US tourists who are out searching for archaeological sites. The two journeys, the search for political refuge and the backpackers' trail, constantly intertwine: early on Fuentes meets the US couple in a roadside restaurant, where (still ignorant about his country) he tells them that accounts of army atrocities are fabrications of the foreign press; later we discover that the tourists are obsessed by a conception of a Latin American culture blood-soaked from an epoch of pre-Columbian sacrifice.

While both natives and foreigners are in some senses looking to turn back time, the tourists are overly fascinated with death, but Fuentes is trying to move past the violence that he's inadvertently uncovering to reach the oasis of peace that, ironically, the Western tourist industry has given him the language to describe.

Finally, this complex and perhaps almost unique film (made by a US director but mostly in Spanish and indigenous languages) maintains a delicate balance between the opposed conceptions of Latin America as utopia and as heart of darkness, between indigenous authenticity and globalized hybridity.

It ends ambivalently and uncertainly: Fuentes fails to find his students, but he does encounter both death and repose; Cerca del Cielo exists, but is no paradise, rather a place of what Sayles himself terms "quiet desperation." It's "where rumors go to die." Still, in its final shot, the film holds out the possibility of yet another más adelante, a continued dream of something better further on.