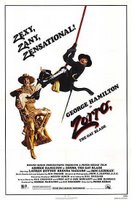

Zorro's back... and now he is two.

In

Zorro, the Gay Blade, when Zorro dies his two sons are called upon to take on his mantle of swashbuckling for justice, and challenging the corrupt

alcalde. One, Don Diego, is the cheeky womanizer of yore; his brother Ramón, however, has changed his name to Bunny Wigglesworth and joined the English navy in line with his rather camper sensibility and alternative sexuality.

So whereas Diego takes up the black suit and hat, Bunny chooses a rather more colorful set of outfits, from plum to lime-green to avocado. He prefers the whip to the sword. And he tells the downtrodden "Remember, my people: there is no shame in being poor, only in dressing poorly!" He is, after all, the gay blade.

Zorro, the Gay Blade

Zorro, the Gay Blade is a spoof, but a very affectionate one. It opens with footage from the classic 1940

Mark of Zorro, and a dedication to that film's director, Rouben Mamoulian. We are definitely encouraged to laugh

with the Zorro franchise, rather than

at it.

For Zorro has always been part-clown as well as part-superhero, even in his very first screen incarnation, in Douglas Fairbanks's

The Mark of Zorro. And,

as I have noted before, the films derive their comedy from the antics of Don Diego as fop, whose bumbling ridiculousness is counterpointed with Zorro's debonair and effortless agility.

It is just that in this movie, these two aspects have been both separated out and collapsed: the two characters, Bunny and Diego, are distinguished; but Zorro becomes an amalgam of both. Zorro here

is the fop, or the fop is Zorro.

Oddly enough, though, this is one of the most overtly politicized Zorros. Perhaps it's only by exaggerrating the theme's cartoonish elements to their most ludicrous extent that some small space is won for something like political commentary. For Diego's love interest here, in one of the movie's few material departures from the standard script, is not the young daughter of an oppressed but noble California family, but rather a Yankee interloper, an apostle for the political freedoms won by the thirteen colonies over on the US East Coast.

(It goes almost without saying, unfortunately, that Bunny has no love interest: his sexuality is all a matter of fashion and innuendo, rather than desire or sex itself.)

So

Zorro, the Gay Blade outlines multiple axes of difference: between rich and poor, gay and straight, but also significantly between Latino and Anglo, or what would today be framed as

chicano and "white."

In his perceptive essay

"The Face of Zorro", Luis Valdez (

La Bamba's director) points out that the Zorro legend has always to be set in that brief and now mythical time of late Spanish or Mexican rule in California:

The fictitious Zorro cannot comfortably survive beyond an 1848-50 story time line without provoking embarrassing questions. By the time California is part of the United States, his foppish usefulness as a critic and foe of corrupt Mexican and Spanish ways is irrevocably gone. There is no place for a Hispanic masked avenger in the new American context.

But

The Gay Blade flirts with contemporaneity, and perhaps that is indeed what makes it the most embarrassing of the Zorro series. Not because it is funny. Not because it is a spoof. Nor even, really, because of its caricatured presentation of homosexuality. No: these elements were always, at least implicitly, in place. Rather, what's most uncomfortable about this movie compared to its predecessors is the way in which it invokes contemporary Anglo-Hispanic race relations.

George Hamilton, playing Diego/Zorro, throughout adopts a thick Hispanic accent. He declares himself, for instance, champion of the "peepuls" and early on Don Diego and his love interest, the WASPy Charlotte Taylor Wilson (played by Lauren Hutton) have a long exchange that revolves around the mispronunciation of "sheep." "Forgive me, but you have a very pronounced accent," she says.

Meanwhile, playing Bunny/Zorro, Hamilton (for it is again he) acts out a fable of Anglo assimilation, whereby racial distinction is blurred, as young Ramón de la Vega adopts an over the top English accent (and as Diego comments to him, "you have a very pronounced accent"), but the mark of difference is preserved, now translated into camp homosexuality.

In short, Zorro "the gay blade" is the first manifestly

chicano incarnation of this character: but now, and no doubt as a consequence, no longer as suave superhero, but as laughing stock.

Labels: difference, zorro