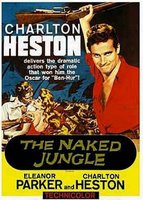

The Naked Jungle

In Italy, apparently, the Charlton Heston / Eleanor Parker vehicle The Naked Jungle goes under the title "Furia Bianca," or "White Rage." The discrepancy between the two titles--one of which highlights the main characters and their affect; the other of which points to the environment in which they are set--indicates the tension that lies at the heart of this movie. There is the story of "man against nature," which was the focus of the Carl Stephenson short story "Leiningen vs the Ants," on which this movie is based; and then there is the melodramatic confrontation between the sexes, played out in the face of natural adversity.

In Italy, apparently, the Charlton Heston / Eleanor Parker vehicle The Naked Jungle goes under the title "Furia Bianca," or "White Rage." The discrepancy between the two titles--one of which highlights the main characters and their affect; the other of which points to the environment in which they are set--indicates the tension that lies at the heart of this movie. There is the story of "man against nature," which was the focus of the Carl Stephenson short story "Leiningen vs the Ants," on which this movie is based; and then there is the melodramatic confrontation between the sexes, played out in the face of natural adversity.Of course, the point is in part that the main characters--pioneer settler Christopher Leiningen, played by Heston, and his mail-order bride Joanna, played by Parker--are themselves forces of nature. The movie suggests that the circumstances of their relative isolation from "civilized" norms, which have to be imposed upon an unforgiving Amazon terrain, reveal a basic difference between man and woman. But it also implies that at the limit, as the reclaimed land upon which Leiningen's cocoa plantation sits is sacrificed back to the river, a more fundamental synergy can be achieved: in the end, gender difference between husband and wife is subordinate to their common humanity when their greatest struggle is simply to stay alive.

The jungle, then, is the great leveller.

And The Naked Jungle is something like a melodramatic Heart of Darkness. Indeed, the movie recalls Conrad's book in its opening scenes, in which we follow Joanna up the river as she comes closer to meeting her husband for the first time. We are led to believe that Leiningen is fearsome and somehow unknowable. Even his best friend, the Brazilian government official who had played the part of Joanna in the ceremony formalizing their proxy marriage, indicates that finally this proudly independent foreigner is a mystery to him. Leiningen has claimed the jungle, but the jungle has also claimed him as one of its own; it is up to the white woman to come and claim him back for humanity.

Yet Leiningen has also established a simulacrum of Enlightenment order in his remote terrain. His sumptuously-outfitted mansion includes a grand piano just waiting for someone to play it; and he prides himself on his humane treatment of his native workers. His is a civilizing mission. Left to their own devices, he claims, the locals would return to their head-hunting ways. But he is not, in the end, so different from his neighbour and rival, the German, Gruber, who whips his charges into submission: Leiningen, too, secures order through force rather than consent, as is indicated when he burns the workers' boats to ensure that they do not flee the plantation when they discover it's in the path of a column of voracious soldier ants, who will destroy everything they come across.

There's no doubt that there's a political allegory here, as DeeDee Halleck implies: the menacing ants are "red" soldier ants, anthropomorphized when Leiningen captures one and holds it up to inspection, and enemies of private property, capitalist enterprise, and individual liberty. What's at stake is the one against the many. But it is not as though capitalism really wins the day.

There's no doubt that there's a political allegory here, as DeeDee Halleck implies: the menacing ants are "red" soldier ants, anthropomorphized when Leiningen captures one and holds it up to inspection, and enemies of private property, capitalist enterprise, and individual liberty. What's at stake is the one against the many. But it is not as though capitalism really wins the day.For in the end, Leiningen is forced to burn his furniture and floods his own fields. In the end it is not capital that survives but the human couple, reduced close to what Giorgio Agamben would term "bare life." Their poverty is absolute.

And it is not the state or the modern biopolitical machine that reduces Leiningen and his wife to bare life. The state here is hardly present, incarnated only in the roving Commissioner who advocates only resignation in the face of the "Marabunta," the ant onslaught, who can at best inform his superiors down-river of what's going on in the heartland. Bare life, here, results at the interface of savage capitalism--accumulation at its most primitive, which is also its most immediately colonial, civilizing--and a natural multitude that springs from nothing and is headed no-one knows where.

The Amazon is imagined as the setting for this grand encounter. But also the setting, simultaneously, for humanity's discovery of its most basic affect: love. A love that dispenses with purity, that accepts that it is use, rather than exchange, that determines value.

In this sense, and no doubt against its intentions, conscious or otherwise, there is something strangely revolutionary about The Naked Jungle.

[Update: Or perhaps not so unintentionally, as I learn that blacklisted writer Ben Maddow was involved with the script. Via Dan Webster's Movies & More.]