Born in East L. A.

Cheech Marin's Born in East L. A. is a Chicano take on "Latin America on Screen." Marin takes the questions of border permeability, national security, and identity's performativity, ironizes them, and attempts to milk what comedy results.

Cheech Marin's Born in East L. A. is a Chicano take on "Latin America on Screen." Marin takes the questions of border permeability, national security, and identity's performativity, ironizes them, and attempts to milk what comedy results.Marin plays Rudy, a fairly thoroughly deracinated Los Angelino (who speaks no Spanish and is completely ignorant of Latino music, for instance), who by one of those strange mix-ups finds himself taken to be an illegal and deported to Mexico. He then spends most of the film attempting to cross back over the border, hustling for money with which to pay a coyote, and falling in love with a beautiful young Salvadoran woman, Dolores.

The romantic subplot, though at first sight (like, frankly, much else in this rather incoherent movie) incidental to the main narrative, is in fact significant. For the film shows the process by which Rudy's desires and habits are re-engineered as he learns to become Mexican--or perhaps assume his own mexicanidad. At the outset he trawls round Silverlake and environs in pursuit of a leggy redhead with a French accent. Indeed, the whole community's desire seems to be concertedly fixated on this vision in a skimpy green dress: whenever he stops to ask passers-by if they have seen a redheaded woman recently, as one they turn and point in the direction she has gone; they have been tracking her movements, but she has also been synchronizing their gaze.

Once in Tijuana, however, Rudy learns to appreciate the perhaps more homely virtues of the latina woman, as he also accepts that as far as US immigration is concerned, he himself for all his protestations of US citizenship is as shifty and untrustworthy as the next wetback seeking work north of the Rio Grande. (Of course, it hardly hurts Dolores's case that, though she lives in a trailer and cooks Rudy arroz con pollo, she does so in an immaculate white strapless cocktail dress.)

So by the end, far from asserting his difference from his brown brethren by insisting on his rights as a citizen, Rudy not only gives up his place in a coyote's truck to a more deserving border-crosser, but also like some Chicano Moses leads a flood of Mexican humanity across the frontier, overwhelming the border police's attempt to stem the tide, all to a soundtrack of Neil Diamond's "America".

For sure, this is the film's ideological blindspot: the United States remains very much the Promised Land; while Mexico is dirty, corrupt, and dangerous, paradigmatically experienced in and as prison. Still, there are wrinkles even here to this binary dichotomization. For instance, an apparently harmless and helpless middle aged gringo couple in their winnebago turn out to be up to their necks in smuggling.

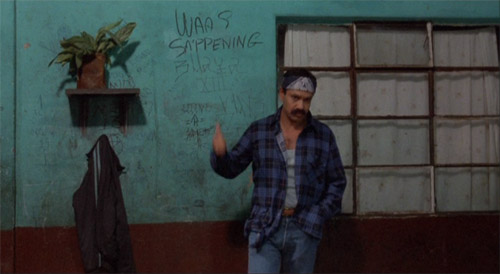

Above all, Chicano identity (at least) is revealed as a set of discrete and transferable gestures and vocalizations. Rudy teaches a group of Asian (Chinese or Korean) immigrants how to pass in East LA: a bandana properly tied and cocked; one hand thrust into a jeans pocket, the other lazily waved behind; and the all-purpose exclamation "Waas Sappening." So if the film evidences some ambivalence as to whether Rudy learns to become Mexican, or rediscovers his forgotten heritage, ethnicity in the United States is seen to be thoroughly constructed.

And just as Rudy plays a German folk song (picked up as a GI in Europe) to seduce appreciative European tourists to part with their money, so he teaches a band of Mexican buskers to play rock and roll. Though Mexico may still (just) be a cradle of authenticity, it can also be a site for the experimentation in multiple identities and identifications, preparing the intrepid for the risky step of crossing the border and claiming all the same rights and benefits as those actually "born in East LA."

Labels: border, performativity