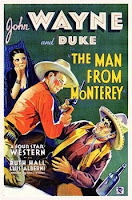

The Man from Monterey

The Man from Monterey (1933) stars John Wayne as Captain John Holmes, an all-American hero who saves Don Jose Castanares from loosing his ranch to land grabbers and his daughter to a sham marriage in pre-Union California.

The Man from Monterey (1933) stars John Wayne as Captain John Holmes, an all-American hero who saves Don Jose Castanares from loosing his ranch to land grabbers and his daughter to a sham marriage in pre-Union California.The opening scene presents the premise of The Man from Monterey: The unscrupulous Don Pablo Gonzales is planning to acquire the ranch of long-time friend Don Jose Castanares by keeping him ignorant of an ultimatum by the United States government that Californians must register their lands by a certain day, or they will be turned into public domain. To ensure that he can claim title to this land, Don Pablo arranges for his dull and pithless son Don Luis to marry Don Jose’s spirited daughter Dolores. Subsequently, the bombastic Mexican sidekick is introduced to the plot, who achieves comedic effect by constantly repeating his long-winded name, Felipe Guadalupe Constacio Delgado Santa Cruz de la Varranca. He teams up with Captain John Holmes after Holmes valiantly steps in as Don Luis is victimizing him. This is the first of numerous run-ins between Holmes and Don Luis in which the former proves himself the better man.

Dolores falls for Holmes after a spectacular display of chivalry, using his fine horsemanship to save her in her runaway carriage after its driver was shot off by bandits. Little do they know that the bandits were hired by Don Luis so that he could display his chivalry, but instead he watches impotently from the sidelines. Holmes, a cavalry officer, has been charged with informing Don Jose that he must register his lands, so Don Pablo hires some American thugs to detain him. A fellow officer shows up and threatens to arrest their leader Jake Morgan, but Holmes skillfully defuses the situation, thereby earning an ally in Morgan. Don Pablo ups the ante by having Don Jose kidnapped, and tells a grieving Dolores that he cannot help her unless she concedes to marrying his son, which she woefully does.

At first Holmes suspects the Morgan gang, but after pinning the kidnapping on Don Pablo, he hatches a plan to infiltrate the wedding. Don Luis’s mistress Anita is employed to masquerade as Dolores, which she does by remaining veiled until the vows have been taken, meanwhile Holmes locates and rescues Don Jose, making use of a cross-dressing Felipe as a diversion. A duel ensues between Holmes and Don Luis, and just when Holmes is being overwhelmed by men loyal to Don Luis, a bizarre psychic communication occurs between the cowboy and his horse, who gallops to the Morgan gang and brings them to assist Holmes. With the conspiracy uncovered and its perpetrators defeated, Holmes and Dolores throw themselves into an embrace which brings the film to a close.

The Man from Monterey is set when America gained sovereignty over California at the end of the Mexican-American War (1946-1948) and portrays its shifting demographic and political character. Firstly, Anglo Americans are moving into the newly acquired territory, which is not appreciated by the Gonzaleses, the younger of which sneers: “As far as I’m concerned, gringos are all robbers.” There is truth to this statement; the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) is one of the biggest land-grabs in history, when the U.S. forcibly incorporated almost half of Mexican territory. However, the filmmakers took pains to make U.S. hegemony appear benevolent; as Holmes explains to Don Jose: “The government has taken these measures for your protection, not to rob you. In no other way can we protect you from all the land-grabbers in California.” At the same time, Holmes tells the Morgan gang, “If I can’t persuade [Don Jose] to register his land, you can move in as fast as the law allows.” Benevolence only goes so far as American interests are concerned. There is a racial difference between the darker-skinned Mexican common-folk and the Hispanic upper class who fret about their land entitlements from the King of Spain; there is an implication that the Hispanic characters do not truly own the land, nor do the mestizo Mexicans, whereas the American characters speak of their right to it.

The supposed benevolence, orderliness and fairness of U.S. hegemony are embodied in the person of John Wayne. This establishes America as an idealized masculine power, in comparison with Europe, embodied by the incapable Don Luis, and Mexico, embodied by the servile Felipe. Wayne epitomizes the masculine ideal by being supremely competent in his every endeavor; he is a just and thorough lawman, a suave and successful lover, and a skilled and valiant fighter. Dolores pines for a man of “energy and ambition” and Holmes excels in both. The other male protagonists starkly contrast to the hero. Don Luis is a mean-spirited and deceitful person, so impotent that he stands by while Holmes steals Dolores and he relies on his aged father to carry out their plot. Felipe is emasculated on numerous accounts including his dog-like devotion to Holmes, his childish superstitions about fortune-telling cards, and ultimately donning the clothes of an old woman. These allegorical figures allow the spotlight to fall on Wayne, an icon that fuses Americanness and masculinity like few others have done.

Labels: geopolitics, masculinity, mexico, westerns