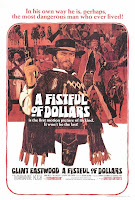

A Fistful of Dollars

A Fistful of Dollars (1964) has a fascinating lineage; the film was directed by an Italian, who based it on Yojimbo (1961) by Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, who in turn was influenced by the Westerns of John Ford. The film was shot in Spain and takes place in Mexico, but it is also profoundly American with its choice of hero and thematic preoccupations. Clint Eastwood is this hero, a tough-as-nails mercenary who becomes embroiled in the feud between two families for supremacy over the town of San Miguel. Eastwood plays them against each other until he is the last man standing on a dirt road littered with corpses, and San Miguel is finally purged of its criminal population.

A Fistful of Dollars (1964) has a fascinating lineage; the film was directed by an Italian, who based it on Yojimbo (1961) by Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, who in turn was influenced by the Westerns of John Ford. The film was shot in Spain and takes place in Mexico, but it is also profoundly American with its choice of hero and thematic preoccupations. Clint Eastwood is this hero, a tough-as-nails mercenary who becomes embroiled in the feud between two families for supremacy over the town of San Miguel. Eastwood plays them against each other until he is the last man standing on a dirt road littered with corpses, and San Miguel is finally purged of its criminal population.The film opens with Eastwood, who is sparsely referred to as Joe, riding into the sun-parched and seedy San Miguel. He befriends the barman, Silvanito, who describes the local politics: The town is run by two competing families, the family of the town sheriff, John Baxter, and the Rojos brothers which include the prudent Don Miguel, the reckless Esteban, and the intelligent and ruthless Ramon, who is the leader. Silvanito says, “They’ve enlisted all the scum that hangs around on both sides of the frontier and they pay in dollars.” Joe does not mind being employed alongside this scum, so he solicits Don Miguel and Estaban for work and they hire him. Ramon is introduced when, after killing an American cavalry squadron and donning their uniforms, his men lure the Mexican military to trade gold for American guns and instead massacre every last soldier. The massage is clear that Ramon means business.

Joe remains indifferent to San Miguel politics meanwhile he plays the Baxters and the Rojos against each other, and extorts money from both. However, something changes in Joe after he witnesses the Rojos trading a Baxter hostage for Marisol, a woman he has been told that Ramon is madly in love with. During the trade-off, Marisol is spotted by a wailing child, and she runs to him with an agonized, tear-stained face to embrace him and his father, before being torn away by Ramon. Silvanito tells Joe that Marisol was taken for ransom after Ramon accused her husband of cheating at cards, and that he threatened to kill the child should her husband resist. That very night, Joe slaughters the men guarding Marisol, leads her to her husband, thrusts a wad of bills into her hand and directs the thankful trio to the United States. Ramon apprehends Joe and has him brutalized, but despite being too battered to walk upright and having one eye swollen shut, Joe is still sharp enough to engineer his escape.

Ramon is crazed with anger and hell-bent on retribution; he launches a manhunt for Joe with orders to torture Silvanito and torch any building that Joe may be hiding in. A broken and tattered Joe drags himself to the coffin-maker, the only other man in town besides the Baxters and Rojos who makes money, and the kindly man evacuates him from San Miguel in a coffin. As they ride by the Baxter homestead Joe peeks out from under the lid to witness a scene which is the pinnacle of excessive violence in the film; the Rojos engulf the home in flames and as Baxters come stumbling out, choking on smoke and shouting their surrender, the Rojos gun them down with cruel enjoyment. Even Eastwood, with his trademark passive face, is visibly sickened by this spectacle, and in the following days he spends recuperating, one can see his hardened resolve to eliminate the Rojos. Just as the Rojos are torturing Silvanito, Joe emerges from billows of dynamite smoke and proceeds to have a climactic shoot-out with Ramon, who he astounds by hiding a bullet-proof breastplate under his poncho. After the last body hits the ground, Joe bids Silvanito and the coffin-maker farewell, taking no reward with him other than the satisfaction that between him and Ramon, he had the faster draw.

A Fistful of Dollars is a cynical film in that noble human emotions are glimpsed only a few times in comparison to the selfishness, rage, jealousy, deceitfulness and cruelty portrayed. Yet even the most honorable action, of Joe enabling Marisol to escape, was not based on any moral code. When Marisol asks, “Why do you do this for us?” Joe answers, “Why? I knew someone like you once and there was no one to there to help. Now get moving.” He could just as easily have not done this, like at the beginning of the film when Ramon’s men shoot at Marisol’s child and Joe merely stands by. A Fistful of Dollars is unlike typical Westerns in that the hero does not act upon moral ideology but impulses; he has no complex back-story to help the viewer understand his motivations.

The “frontier” looms large in A Fistful of Dollars. For Marisol, the border is a gateway to a better world in which Ramon has no jurisdiction. However, the border is more generally portrayed as lawless zone where the arm of state power fails to reach, and thus the most degenerate elements of both societies, from Mexican crime-lords to shiftless Texan drunkards, congregate there. Unlike in the Westerns of previous eras, in which the frontier was replete with promise, or at the least kept under control by the hero, frontier lawlessness in A Fistful of Dollars is beyond the scope of any one man. However, after a massive amount of bloodshed, Joe does manage to save San Miguel from the clutches of criminality. The violence in A Fistful of Dollars takes many, often brutal forms, but it is ultimately justifiable because of its cathartic role. In order to become a civilized place, San Miguel must endure its darkest hour of savagery, from the hero as well as from the villains.