Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Two American outlaws escaping to Bolivia at the turn of the century seems like improbable concept for a movie, but Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is loosely based on the real lives of Robert LeRoy Parker (alias Butch Cassidy) and Harry Longabaugh (alias the Sundance Kid). The history of this notorious duo is an amalgamation of fact, hearsay, journalistic sensationalism and American Old West mythmaking. What director George Roy Hill offers is a portrait of a powerful friendship that stayed true under the stresses of pursuit by lawmen who wanted them dead or alive, love for the same woman, relocation to a foreign continent, and the impossibility of escaping their past.

Two American outlaws escaping to Bolivia at the turn of the century seems like improbable concept for a movie, but Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is loosely based on the real lives of Robert LeRoy Parker (alias Butch Cassidy) and Harry Longabaugh (alias the Sundance Kid). The history of this notorious duo is an amalgamation of fact, hearsay, journalistic sensationalism and American Old West mythmaking. What director George Roy Hill offers is a portrait of a powerful friendship that stayed true under the stresses of pursuit by lawmen who wanted them dead or alive, love for the same woman, relocation to a foreign continent, and the impossibility of escaping their past.Early in the film, Cassidy (played by Paul Newman) explains his plan to Sundance (played by Robert Redford) to go prospecting in mineral-rich Bolivia. Cassidy is the brains of the operation while Sundance is a lightning fast gunslinger. When they return to the Hole in the Wall Gang hideout, a member challenges Cassidy for its leadership. Cassidy boots him in the crotch then appropriates the idea of robbing the Union Pacific Flyer twice, for its owners would refill the train with money not expecting a robbery on the return trip. After a successful hold-up, Cassidy and Sundance gloat on a balcony overlooking the mayor, who is ineffectually trying to rally townsfolk to catch the Gang. We meet Etta, who while being the devoted girlfriend of the gruff and reticent Sundance, has a tender relationship with the affable Cassidy. This is illustrated in a dialogue-free interlude where they ride a bike and monkey about in the countryside to the soundtrack of “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head.”

The mood becomes darker and strained when, after they are surprised during the second train robbery by cavalry hired by the railway tycoon, they are forced into a lengthy chase sequence. The Hole in the Wall Gang splits in separate directions, but the pursuers follow Cassidy and Sundance. They are betrayed while hiding out at a brothel and denied amnesty by a friendly sheriff, who tells the pair of their inevitable demise. The posse tracks them through the night and the next day with amazing skill and persistence; the pair determines that among them are the expert Indian tracker Lord Baltimore and notoriously tough lawman Joe Lefors. Cassidy and Sundance are pursued over much terrain before being forced to jump from a cliff and be carried away by the rapids far below. They end up back with Etta and learn that E.H. Harriman, the railway tycoon, put together the outfit to stay on their track until they were killed. At this point they decide to go to Bolivia, and Etta states her intent to go with them, but adds ominously that she wants to be absent when they are finally killed.

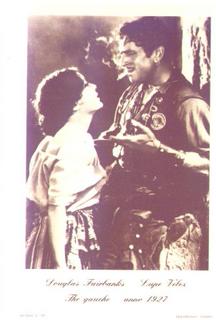

The journey is illustrated in a series of sepia photographs. When the trio arrive in their Bolivian destination they are dismayed by its rustic appearance, and Sundance curses Cassidy for his harebrained ideas. They resume their criminal life after Etta gives the men Spanish lessons with “specialized vocabulary” for bank hold-ups. A humorous sequence shows the pair blundering through a robbery with a Spanish crib-sheet, and struggling to recite with Etta phrases such as “This is a robbery. Esto es un robo.” Soon their routine is perfected and they are living decadently, with wanted posters for the “Bandidos Yanquis” showing their notoriety. The honeymoon is over, however, when a potential sighting of Joe Lefors scares Cassidy into wanting to go straight. The men are hired as bodyguards for a humble and eccentric American mine owner, which they fail at when Bolivian bandits kill him. Being forced to kill the bandits shakes Cassidy, who has never killed a man, and the pair decide to return to robbery. Etta, perhaps with a premonition of their demise, leaves the next day. In the town of San Vicente, a boy recognizes a stolen mule and alerts the police to the outlaws. The police descend upon them, starting a climactic shoot-out in which Cassidy and Sundance are seriously wounded due to lack of ammunition. While the bloodied men are recovering strength in an abandoned building, poignantly discussing their next destination of Australia, the Bolivian military gathers outside. When the pair unwittingly exits the building, the camera captures them in a sepia-toned freeze frame to the sound of repeated volleys of rifle fire.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid enthralled the American public, evidenced by being amongst the 100 highest grossing films of all time (adjusted for inflation) and multiple Academy Award accolades. The pathos generated by the close male friendship between the outlaws, who are bound to meet with an untimely death, plus their fetching yet vulnerable female counterpart, largely accounts for the film’s appeal. However, the heroes are also partly conceived as Old West Robin Hoods, an archetype with universal appeal. Partly so because they rob from the rich and keep for themselves. In the United States, the noose of capitalism and modernity tightens around Cassidy, an older cowboy who remembers freer and simpler times; he curses the newly impenetrable banks, the immensely rich and powerful railroad barons, and the bicycle, a modern invention that threatens to replace the horse. He rebels against this by blowing up trains and appropriating easily and ill-gotten wealth, but then is forced to escape to Latin America. In doing so, Cassidy steps multiple decades back in time. Bolivia recalls California in the height of the Gold Rush, when humble but hardworking folk could become rich, not just aristocratic sons who inherit railroads. The charmingly outdated Bolivia is the only apt place for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, symbolic of the romantic frontier spirit outmoded by the modern commercial one, to meet with their inevitable death.