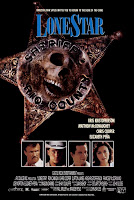

Lone Star

Lone Star (1996) follows Sam Deeds, a cynical Texas sheriff, as the discovery of a forty year-old skeleton in the desert prompts him to unravel the complex histories of his community. The film goes beyond the typical crime drama in that its plot serves as a vehicle to explore contemporary multiculturalism and the politics of history.

Lone Star (1996) follows Sam Deeds, a cynical Texas sheriff, as the discovery of a forty year-old skeleton in the desert prompts him to unravel the complex histories of his community. The film goes beyond the typical crime drama in that its plot serves as a vehicle to explore contemporary multiculturalism and the politics of history.Lone Star begins with two men searching for old bullets in a Rio County desert, once used as a military firing range, when one stumbles upon a half-buried skeleton with a sheriff’s badge and Masonic ring. They call Sheriff Sam Deeds (played by Chris Cooper) who takes an immediate personal interest. Subsequent scenes highlight the racial dynamics of Rio County; the coexistence of Latino, Black, Native-American and White communities is tense due to historical strife, current inequalities and racial prejudice. Sam arrives in the midst of three old men reminiscing about his father Buddy Deeds. Even though Sam is clearly pained to be living in his father’s shadow, a man with legendary status, he asks that mayor Hollis Pogue retell his story. Back in 1958, Hollis and Buddy were deputies for Sheriff Charlie Wade, infamous for his corruption and ruthlessness. In a flashback, Buddy threatens Wade to leave town because folks are sick of living under his thumb, and the next day Wade disappears with $10,000 of county money. The rest of the film will be concerned with uncovering the many facets of this legendary character.

Meanwhile, another legend is being discussed. Pilar Cruz (played by Elizabeth Peña) debates with fellow teachers about how the Battle of the Alamo ought to be taught; every opinion is hot-headedly voiced from the staunchly orthodox to radically revisionist. Pilar and Sam were high-school sweethearts but their parents forbade the relationship so they parted ways; they exchange only a few terse conversations after the passage of many years. Sam is certain that the skeleton belongs to Charlie Wade, and resolves to determine whether it was his father who killed him. Sam attempts to pry into the memories of the older generation for clues, but finds that characters such as Hollis and Otis Payne, owner of the only bar where African-Americans feel welcome, have great affection for Buddy and are reluctant to share details of the night that Wade disappeared. However, he discovers that Buddy had an ambivalent sense of morality. Unlike his scoundrel of a predecessor, Buddy is remembered as being benevolent and just, however he would overlook minor infractions in return for favours. Only one individual speaks negatively of him, telling Sam about how he had a Mexican community removed from where he thereafter bought cheap lakeside property. Sam is motivated by the search for truth, but he is also resentful of the universal admiration for his father; if Buddy was a murderer Sam wants the world to know.

The director intermittently turns his lens to the lives of sub-characters, whose storylines portray experiences with racism and generational differences in social attitudes. Notable among these characters is Pilar’s mother, who is merciless with the illegal immigrants she employs and calls the border patrol when she spots new arrivals from her back porch. Meanwhile, Sam fills in more pieces of the puzzle. The bullet collectors from the beginning find a Colt 45 pistol shell amongst the customary M1 rifle shells; this was the type of gun Buddy used. Sam also goes down to Mexico to hear the story of how Wade killed a man named Eliano Cruz point-blank for transporting illegals, told by a survivor of this incident. The final piece falls into place when an acquaintance drops the fact that Buddy had a mistress, prompting Sam to search his father’s belongings until he finds a love letter from none other than Pilar’s mother. When he confronts Hollis and Otis about this, they spill the entire story; Wade found young Otis running after-hours gambling and was about to kill him when Buddy burst into the bar, in the moment when Hollis shot Wade in horror. The three buried Wade, taking money from the safe to make his disappearance seem realistic and gave it to Cruz’s widow, who Buddy later conceived Pilar with. Sam, who in the course of his journey mended his relationship with Pilar, reveals this history to her, but despite their blood relationship they decide to be together. Her words which close the movie offer an apt maxim for generations striving to overcome historical prejudice: “Forget the Alamo.”

Lone Star is a meditation on how a multicultural community, in which each racial group differently experienced the traumas of war, displacement and slavery, strives to write an all-encompassing political history and overcome prejudice to peacefully coexist. The investigation Sam undertakes to determine how Wade died is a metaphor for the process of writing political history; not only is it difficult to recover the exact deals, but history is influenced by the subjective viewpoints of its authours. In the end he settles with the hybrid of truth and myth that is palatable to most people.

Lone Star has a well-developed narrative on the U.S.-Mexico border which spans from the deeply conservative fear of loosing a clear demarcation between superior and inferior “civilizations,” to the liberal opinion that borders are “invisible lines” imposed by governments to the detriment of fundamentally equal human beings. The border is portrayed as porous, but only one way; Sam takes it for granted that he can spend the afternoon in Mexico, while Mexicans risk their lives to cross the border. The relationship between Sam and Pilar is a metaphor for that between the U.S. and Mexico; the two were always bound together by blood and experienced eras of alienation from each other. The fact that the pair wish to forget history and embark on an incestuous relationship certainly indicates the director’s optimism about future U.S.-Mexico relations.