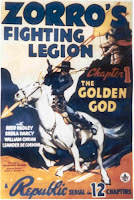

Zorro's Fighting Legion

Zorro's Fighting Legion, a popular and critically well-regarded twelve-part serial from 1939, takes our masked crusader away from his native California, placing him at the heart of newly-independent Mexico. The young republic is still struggling to find its feet, and the opening seen anachronistically portrays Benito Juárez urging the local councilors of a place called San Mendolito to come to their country's aid. Their region contains Mexico's most important gold mine, whose product is needed to establish foreign credit, buy arms, and shore up the fledgling democracy. Unfortunately someone or something in San Mendolito has altogether other ambitions.

Zorro's Fighting Legion, a popular and critically well-regarded twelve-part serial from 1939, takes our masked crusader away from his native California, placing him at the heart of newly-independent Mexico. The young republic is still struggling to find its feet, and the opening seen anachronistically portrays Benito Juárez urging the local councilors of a place called San Mendolito to come to their country's aid. Their region contains Mexico's most important gold mine, whose product is needed to establish foreign credit, buy arms, and shore up the fledgling democracy. Unfortunately someone or something in San Mendolito has altogether other ambitions.The local Yaqui Indians have been visited by their mythical golden god, one Don-del-Oro, who is stirring them up to rebellion in the name of vengeance against the white man and the deity's own dreams of overthrowing the Republic and installing himself as Emperor. The Indians, with the help of various local thugs, are to divert both gold and munitions to this treacherous plot. Moreover, the rebels have friends in high places, as half the councilmembers seem to be on their side. Can it be, indeed, that Don-del-Oro is no god but rather a local notable dressed up in clumsy fancy dress?

Here comes Zorro (and his legion of well-wishers and similarly masked helpers) to uphold the rule of law and figure out the mystery. It takes him the whole of the twelve episodes, but yes indeed Don-del-Oro proves to be (wait for it) the local Chief Justice. Hence in a curious symmetry, our hero, with his double life as both foppish dandy Don Diego black-clad avenger Zorro, is faced with an enemy who is similarly doubled: a respectable councilmember who takes on the guise of fiendish pagan idol. What's more, it is only when disguised that each reveals his true nature: Zorro's as the dashing and virile hero; Chief Justice Pablo's as faithless enemy of the nation. And the final irony is that it is the bandit who most ferociously upholds the rule of law, while it is the judge who does everything in his power to circumvent or abolish it.

Of course, our sympathies are steadfastly with Zorro: Don-del-Oro is by turns comically robotic and a sinister rabble-rouser. But if we stop and think about it, old metalhead has a point when he denounces the injustice of the white man taking away indigenous gold. Indeed, for most of the serial's twelve episodes Zorro's patriotic zeal is such that the rather forgets to stand by the downtrodden, and happily shoots at indigenous people if and when they stand in his righteous way. It is only at the very end that he figures out that the best way to avoid a subaltern insurgency is to establish some kind of rapprochement between indigenous and white: by saving the tribal chief's life and showing him that the people's god is just a guy in a yellow suit, Zorro presents himself as friend of the Yaqui and blood brother to main man Kala.

But if the story is a warning against the dangers of populism, much like The Wizard of Oz (which came out the same year), the danger of placing the action in a real country rather than in a magical land is that it's harder to elide the real force of populist demands. Fortunately for the film's logic, these Yaqui Indians are invested with all the humanity of Oz's munchkins. But then that merely makes the final turn to seal a peace treaty with these credulous and barely clothed savages all the more curious. Zorro evades the problem by heading back to California as soon as the action is over: mission accomplished; he's won the war south of the border, so why should he stick around to deal with the complex problems of daily governance?

What drives the serial is the tension of the end-of-episode cliffhanger. Eleven times in a row, Zorro has to extricate himself from the diciest of predicaments (a severed rope bridge, a plunging mine elevator, a rampaging flood, an incredible shrinking room). Each time we are left briefly to wonder "What happens next? Will our hero ever survive?" But it is his final extrication, from the perils of peace and the fragility of liberal hegemony, that should give us most pause for thought.

Now how will he get out of this one?

Now how will he get out of this one?YouTube Link: the final confrontation with Don-del-Oro.